In this week's blog post, continue our focus on Queen Louise of Prussia. Last time, we gave an overview of Queen Louise’s short but influential life. Now we will go in-depth into her interactions with Napoleon in the immediate aftermath of the disastrous campaign of 1806, their famous meeting at Tilsit in July 1807, and Louise’s role in rebuilding Prussia.

Following the calamity at Jena and Auerstedt, Louise and her sons escaped to Königsberg. The state administration had effectively ceased to function, and the royal family made a difficult journey from town to town and barn to barn. From Berlin, Napoleon attempted to break any further Prussian resistance and to undermine the Russo-Prussian alliance. He did so by attempting to discredit Louise through the publication of a series of bulletins which portrayed her as the main instigator of the war and spread rumours about the nature of her relationship with Tsar Alexander.

Soon after Louise was reunited with the King at Königsberg, rumours abounded that the enemy was advancing on the city. Despite being ill with typhoid, the Queen braved the cold winter to travel to Memel, declaring that she would rather sacrifice her life than fall into the hands of Napoleon. The Prussian court remained in Memel for a year, pushing the infrastructure of the small East Prussian town to breaking point.

Frederick William and Louise's temporary residence at Memel (now Klaipeda, Lithuania)

Despite the misery of the situation, the Queen remained defiant. There were minor successes to celebrate. The Russians and Prussians had fought Napoleon to a bloody standstill at Eylau, prompting Napoleon to send General Bertrand to Memel in an effort to make peace and isolate the Russians. Bertrand attempted to persuade Louise to throw her weight behind a peace settlement, but she dismissed the offer out of hand. Louise trusted in the Russian alliance, and Alexander was more than happy to play the role of the knight in shining armour.

Faced with the continued Prussian rebuttal of his peace overtures, Napoleon duly laid siege to a string of Prussian fortresses in East Prussia. The defiance of the Prussian garrison at Kolberg against French besiegers provided another glimmer of hope, though Louise was disappointed by Bennigsen’s refusal to relieve the siege of Danzig, the fortress falling to the enemy on 24 May. She was bold enough to write to the Tsar advising him to dismiss his commander. Her concerns were realised when Bennigsen allowed his army to be trapped at Friedland on 14 June. Unlike at Eylau, the Prussians did not reach the field in time to save the day.

Following the defeat at Friedland, Napoleon occupied Königsberg and Louise prepared to evacuate once again, this time across the Russia border to Riga. News that Bennigsen had agreed to a four week truce for peace talks stabilised the situation and Louise could now stay in Memel, but she was far from optimistic about the immediate prospects of her kingdom. Having seen Napoleon sweep away a host of German rulers and force Kaiser Francis to abolish the Holy Roman Empire, Louise had every right to expect that she and her husband would lose their thrones.

The Russian army was demoralised and Alexander was ready to negotiate. Louise and Frederick William’s hopes for an acceptable peace settlement rested with the Tsar. On 25 June the French and Russian emperors met for the first time at Tilsit. Frederick William could only watch from the sidelines and described the arrangements in a letter to his wife:

“This afternoon [the Tsar] set out for the Tilsit bridge. It has been burnt down; but Bonaparte has had a sort of raft constructed in the midstream of the river. On this there is a pavilion, and the two emperors (not your humble servant, he will have that felicity tomorrow) set out from the opposite banks at the same time. I watched the proceedings from a distance so that I might learn how to act my part properly. I put on my Russian cloak and took up my position with the Russian officers on the margin of the river.”

Napoleon and Alexander's meeting at Tilsit

This scene encapsulated Prussia’s reliance on the Tsar of Russia. While Alexander had managed to win a handful of concessions for his unhappy ally, it was clear that Napoleon intended to turn the proud kingdom into a French puppet. Napoleon had sought the dismissal of Hardenberg, the chief minister of Prussia who had been an unyielding opponent of French policy. Napoleon’s refusal to entertain Hardenberg forced Frederick William to rely on Field Marshal Friedrich Adolf von Kalckreuth as his chief negotiator with Napoleon. In her response to Frederick William before his meeting the following day, Louise advised him: “Do not yield a hairsbreadth to any demand which is calculated to undermine your independence. Misfortune has surely taught us this great lesson… that the loss of territory is as nothing in comparison with the loss of liberty.”

As he wrote his letter to his wife, Frederick William was not to know that Tsar Alexander had proven unexpectedly receptive to Napoleon’s proposal for a Franco-Russian alliance. When he met Napoleon the following day, the King understood that he was an afterthought for the almighty conqueror. Queen Louise supposed that Napoleon would either keep her husband on the throne as his puppet, or be rid of him altogether and gift Prussia to one of his brothers.

Napoleon had indeed entertained thoughts of the latter, and it was thanks to Tsar Alexander’s intervention that Frederick William was not entirely dispossessed. What came to pass was almost as bleak. To the east, the Duchy of Warsaw was carved out of the Prussian portion of the partitions of Poland, while to the west Prussia’s Rhenish possessions were granted to Jerome Bonaparte, King of Westphalia.

Map of Prussia's territorial possessions. Prussia retained the orange parts at Tilsit.

Frederick William could not hide his indignation in letters to his wife, though was not bold enough to raise any objections in Napoleon’s presence. While he remained convinced of the Tsar’s personal favour, he could see that Alexander had been charmed by Napoleon and could only do so much for Prussia. Out of ideas himself, one of the King’s ministers, perhaps passing along a suggestion from the Tsar, proposed that the Queen should have an interview with Napoleon to plead Prussia’s cause.

Frederick William was not terribly keen on the idea, and while Louise indicated that she was ready to make any sacrifice for her country, she detested the prospect of meeting the “beast.” On 5 July, she met with the Tsar and Hardenberg and quickly ascertained the state of the negotiations. The following day, wearing an embroidered white robe which glistened in the sun, Louise came face to face with the man whom she loathed more than any other on earth.

Apart from Napoleon and Louise, there was no-one else present at this famous meeting. The Swedish ambassador, Carl Gustaf von Brinkman, left a vivid account of the meeting as described by Louise. Although the Queen addressed Napoleon “as a wife and mother” rather than as a “politician,” the discussion soon turned to political matters. The Queen warned him that the peace he had proposed was “intolerable” and he could not expect It to last for long, while defending her conduct in 1806 on the basis of Napoleon’s double-dealing over Hanover. The Queen prevented her interlocutor from changing the subject at hand to more mundane issues. The mighty Napoleon found it difficult to justify himself, and was later to admit in Saint Helena that “the Queen remained mistress of the situation.”

Napoleon and Queen Louise at Tilsit

That evening Louise and Frederick William were invited to dine with Napoleon and Alexander. The conversation continued in a cordial spirit. Prussian observers sensed that the victorious Emperor of the French might prove to be a modern day Titus and would choose to alleviate Prussia’s suffering, and Louise appeared to briefly entertain such thoughts herself. When the Prussian diplomats received the formal treaty, they saw that the conditions were completely unchanged. The Queen finally appreciated Napoleon’s sadistic streak as he raised the hopes of the Prussian delegation only to dash them against the hard reality of French imperial interests. Faced with no other options, Frederick William was forced to sign the treaty on 9 July.

Queen Louise returned to Memel a broken woman, while her husband contemplated abdication. She was especially aggrieved at being forced to dismiss Hardenberg, and at Tsar Alexander’s decision to seemingly abandon Prussia in favour of Napoleon. On 12 July 1807 Kalckreuth signed the Convention of Königsberg, allowing 40,000 French troops to remain in Prussian territory until Napoleon had managed to extract a sum of 150 million francs as reparations – a sum far beyond the capacity of the Prussian state.

Louise would spend the rest of her life saving Prussia from utter destruction with limited room for manoeuvre. Her show of defiance had given hope to the ‘patriot party’ which advocated radical military and social reforms to strengthen the Prussian state so that one day it might free itself from Napoleonic influence. Louise urged her husband to appoint Baron vom Stein as chief minister. The conservative Frederick William was reluctant to appoint a man who desired radical reforms, but Louise convinced him that he was the only hope for Prussia’s salvation. Napoleon, unaware of Stein’s radicalism and his hostility to France, assented to the appointment. Stein was given wide-ranging powers and did not hesitate to use them. On 9 October, he signed the edict to emancipate all the serfs in the Kingdom of Prussia.

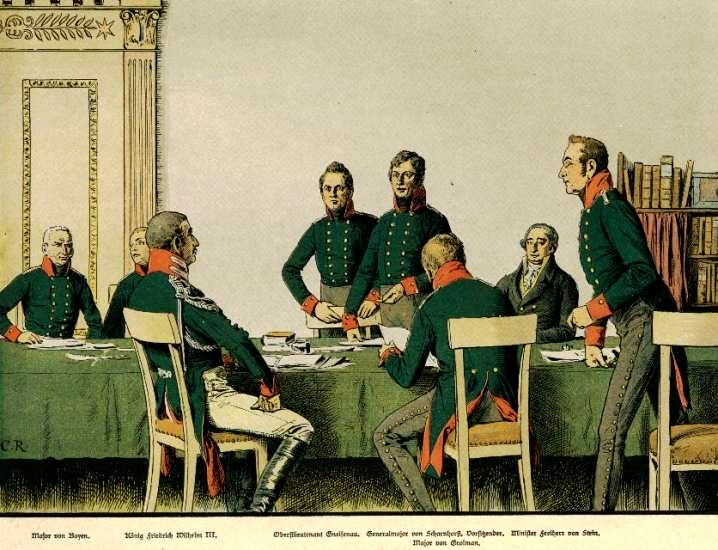

Things began to improve slowly with Stein in charge. In January 1808, the royal family was allowed to take up residence in Königsberg. While Stein was busy with his programme of social reforms, General Gerhard von Scharnhorst was appointed to head the committee tasked with reorganising the Prussian military. Scharnhorst aimed to create a system of conscription that encompassed all social classes, and pioneered a reserve system to circumvent restrictions on the size of the Prussian army. In 1809, Wilhelm von Humboldt was appointed Minister of Education and introduced a system of national education. The King remained suspicious of the reformers, but Louise was always at hand to smooth over any friction that arose.

King Frederick William and the Prussian army reformers

At the same time, Louise dedicated herself to the upbringing of her children. She was particularly close to her eldest sons, Crown Prince Frederick William, and Prince William, instilling in them the ideas of a nascent German nationalism. In a letter to her father from 1809, Louise wrote, “Especially beneficial is it for the Crown Prince to become familiar with trouble before he comes to the throne. He will the better know how to prize and guard the happiness which I hope will be in his future days.”

Dying in 1810, Louise would not see for herself the fulfilment of the enterprise she championed – Prussia’s rejuvenation over the course of the nineteenth century, over which her sons would preside. It is likely she would have lived longer had she not been subject to the physical and emotional suffering inflicted on her by Napoleon. Yet even in death, Louise would have the last laugh. The reforms which she had so eagerly supported allowed Prussia to play a key part in liberating Germany alongside her Russian allies in 1813, entering Paris in triumph in 1814 and once again in 1815. At the Congress of Vienna, with Hardenberg as chief negotiator, Prussia emerged larger and more populous than she had ever been.

Queen Louise’s beloved sons did not forget the indignities they suffered at Napoleon’s hands in the pitiful winter of 1806-07. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and William accompanied his army as it defeated the French at the Battle of Sedan. As he accepted the surrender of Emperor Napoleon III on 1 September 1870, the 73 year old William, soon to be German Emperor, must have recalled events 63 years earlier. Without the efforts of his mother, which consigned her to an early grave, it is doubtful whether Prussia could ever have risen from the ashes of Jena-Auerstedt to eventually bring about German unification.

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!