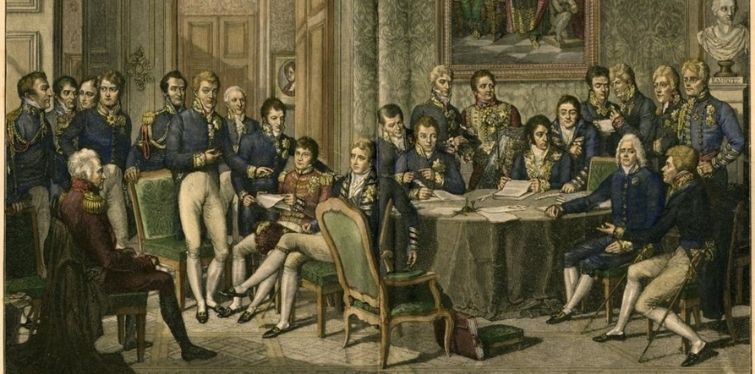

In our last blog post, we offered an overview of Prince Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord’s extraordinary career in the service of successive governments in one of the most tumultuous periods of French history. This time, we take a closer look at his Talleyrand’s tenure as King Louis XVIII’s Foreign Minister before and during the Congress of Vienna of 1814-15, during which he arguably did his greatest service for France.

On 6 April 1814, the Emperor Napoleon abdicated the throne and agreed to go into exile in Elba. Meanwhile, the victorious Sixth Coalition, led by Austria, Britain, Prussia, and Russia, restored the Bourbons to the throne in the portly form of King Louis XVIII. Indeed, Talleyrand had been instrumental in effecting the Bourbon restoration on the grounds of legitimacy, and the French political elite followed his lead. Upon meeting him, however, Talleyrand was not entirely thrilled by his new political master, who was seemingly under the impression that he could simply turn the clock back to 1789 and exercise his power and authority by divine right. Louis made a point of rejecting the constitution handed to him by Talleyrand, but proclaiming his own along similar lines.

King Louis XVIII

King Louis and his ex-emigré ministers attempted to keep Talleyrand out of French domestic politics. Nevertheless, Louis did reappoint him to the Foreign Ministry. Talleyrand would face the challenging task of negotiating with the Sixth Coalition allies to keep as much of French territory as possible. During his 15 years in power, Napoleon had not only transformed France but the whole of Europe. It was up to the Sixth Coalition to decide what would become of Napoleon’s conquests. The allied diplomats hoped that a pan-European settlement could be agreed on within a matter of weeks. The allies had been clear while Napoleon was still on the throne that France would have to give up her conquests beyond the Pyrenees, Alps, and the Rhine. On 23 April, France had signed a full armistice with the ‘Big Four’ and Spain. The terms stipulated that allied forces would evacuated France once French armies were withdrawn from garrisons that lay beyond her borders in 1792. This would prevent France from exercising hegemony over the European continent as Napoleon had done, and while also restoring lost territories to the allied powers.

However, despite the bonds forged between the allied nations on the battlefield in 1813-14, the united front among the allies only went so far. Allied mistrust had never gone away even while they were fighting Napoleon on the field, and their differences came to the fore once Napoleon was out of the way. Each power had entered war for different reasons. Napoleon had humiliated Prussia militarily in 1806 and deprived her of half her territory at Tilsit in 1807. The Prussians sought retribution and suggested that Prussia should be indemnified by France to the tune of 170 million francs for war damages. While Tsar Alexander of Russia had no particular interest in seeing the dismemberment of France, he was ill-disposed to the Bourbons and his skepticism appeared to be well-founded. Despite being France’s traditional enemies, Austria and Britain hoped to maintain her as a first rate power – largely to counterbalance growing Russian influence.

Talleyrand, negotiating on behalf of King Louis, saw the opportunity in front of him. He knew that the allies would be unable to agree on a Europe-wide settlement. Tsar Alexander wanted to restore the kingdom of Poland as part of the Russian Empire, while the Prussians claimed the whole of Saxony and a host of Rhenish territories. Britain and Austria were primarily concerned about Russia projecting its power into central Europe, while Austria was keen to prevent Prussia from becoming the dominant power over the German states. Talleyrand shared the concerns about Russian aggrandisement and Prussian vindictiveness and recognised that France had much in common with Austria and Britain’s position and signalled his support. Meanwhile, Metternich and Castlereagh – the Foreign Ministers of Austria and Great Britain – were inclined to grant a generous peace to France.

Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

Talleyrand managed to prevail on the allies to sign a treaty with France to establish her provisional borders. The full continental settlement would have to wait. On 30 May, the Treaty of Paris was signed between France on one side and Russia, Austria, Prussia, Sweden, Britain, Spain, and Portugal on the other. France would retain several slices of territory beyond the borders of 1792, including the former papal enclave of Avignon, a large slice of Savoy near Geneva, and several towns along the Rhine and the Belgian border. The majority of her colonies – having been captured by the Royal Navy – were restored to her. Castlereagh had shut down the Prussian demand for reparations and France did not have to pay a penny to anyone. Talleyrand could look proudly on a treaty which ensured that France would have ‘nothing to fear for itself and which, threatening no one, will have many friends.’ He handed to Louis XVIII a France that was significantly larger than the one ruled by his late brother, the executed Louis XVI.

In June, the allied representatives were invited to London to celebrate the victory over Napoleon and to continue the discussions, but a few extra weeks was hardly enough for them to come to an agreement. The key issues would have to be decided at Vienna later in the year, at a Congress attended by European potentates and diplomats ranging from the Tsar of Russia to the rulers of the smallest principalities. In the intervening period, Talleyrand made sure to lobby the British ambassadors in Paris (Charles Stewart and later the Duke of Wellington), recognising that British and French interests were closely aligned.

French satirical print depicting the 'dancing Congress,' British Museum Collection

When Talleyrand arrived in Vienna on 23 September, he was still not certain of his status at the Congress. The Big Four was not thrilled about the prospect of Talleyrand – the most skilled diplomat of the age – joining in the key deliberations. Talleyrand desired a seat at the top table not only for France but also lesser powers including Spain and Portugal, whom he believed would support France on most issues. The Congress was initially scheduled to open on 1 October, but the arguments over the arrangements caused the formal opening to be delayed a whole month. After formal proceedings began in November, Talleyrand was soon admitted to the top table and the Big Four had become the Big Five. He had secured his first diplomatic success before the Congress had begun.

Talleyrand had arrived in Vienna with four main priorities:

- That Austria shall not obtain the States of the King of Sardinia for one of its princes.

- That Naples shall be restored to Ferdinand IV.

- That the whole of Poland shall not pass under the sovereignty of Russia.

- That Prussia shall not get the whole of Saxony.

These objectives were based on Talleyrand’s desire to preserve peace in Europe and to secure France from enemy invasion. As with the Bourbon restoration in France, Talleyrand believed that legitimacy was the best way to ensure political stability. Thus, Europe should return to what it had looked like pre-Napoleon as far as possible. Ironically, Talleyrand's prospects of achieving these negotiating objectives were far better in Vienna than in Paris. Tsar Alexander had been the hero of the hour among the Parisians, but the Congress of Vienna was dominated by Metternich, who was as keen as Talleyrand to establish a new European balance of power to preserve the peace. Aside from diplomatic meetings, Vienna was full of sumptuous balls and dinners and had attracted the most glamorous ladies of the age. Talleyrand was in his element.

Klemens von Metternich

While supporting Austria’s efforts to regain her position of dominance in northern Italy, Talleyrand also ensured that Piedmont would be restored to the Kingdom of Sardinia. Naples proved a far tougher nut to crack. The Austrians had previously agreed with Joachim Murat, Napoleon’s brother-in-law whom he installed as King in 1808, that he could retain his throne in return for changing sides. Talleyrand argued that Austria could not make such an agreement because Naples was not theirs to give. The solution to the dilemma came from Murat himself. Anticipating that the Austrians might go back on their word, he took to arms in a vain and farcical attempt to unify Italy which would eventually see him in front of a firing squad. Following Murat’s defeat, the road was open for King Ferdinand IV to return to Naples.

Talleyrand was well aware that not everything could be placed back in Pandora's box. The Holy Roman Empire had been a collection of over 300 German states, and Napoleon had consolidated these into a far smaller number of kingdoms and duchies. There was no question of bringing the Holy Roman Empire back. Instead, the Congress set up the German Confederation, a collection of 39 German states. Its capital would be at Frankfurt with Austria assuming the presidency of the federal structure. Thus, Austria had regained its prior influence over Germany and Italy. Meanwhile, Britain’s interests were limited to securing herself from invasion from the continent. The Low Countries had been a launching pad for invasions of Britain for centuries, and Castlereagh was keen to prevent them from falling under French control. The Congress accepted his proposal for Holland and Belgium to form the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, ruled by the Prince of Orange as King William I.

There remained the question of Poland and Saxony. These issues were interrelated, as Tsar Alexander had agreed to support Prussian designs on Saxony in return for Prussia abandoning its own claims to part of Poland. From the very beginning of proceedings, Castlereagh, Metternich, and Talleyrand drew closer and stood firm against Russian designs on Poland and Prussian designs on Saxony. Alexander first argued that he was seeking to redress the wrong that had been done to Poland, to which Talleyrand indicated assent as long as Poland was independent from the Russian Crown. Alexander then reminded the participants of the large Russian army stationed in Poland, but the others remained unmoved. The Tsar was diplomatically isolated and even some of his own entourage accepted that the demands were unrealistic. As for Saxony, the Prussians would not budge and seemed intent on seizing the kingdom by force, confident in the Tsar’s backing. In early January 1815 Talleyrand brokered a secret treaty of alliance with Castlereagh and Metternich should the Prussians attempt to do so. Less than a year after Napoleon’s defeat, the powers of Europe were threatening to be at war once again.

Tsar Alexander I of Russia

From his Elban exile, Napoleon kept abreast of developments in France and in Vienna, and sensed that the coalition which had defeated him was on the verge of breaking apart. In February 1815 he escaped from Elba and landed in southern France. By 20 March he entered Paris at the head of a large army of veterans who had rallied to his standard. The news shocked the allies who temporarily stopped their bickering and formed the Seventh Coalition. Austria, Russia, Britain, and Prussia each agreed to field 150,000 men in a final campaign to get rid of Napoleon for good. The campaign would reach a climax with Napoleon’s defeat by Wellington and Blücher at Waterloo on 18 June 1815. Napoleon was forced to abdicate for a second time on 22 June. Once again Talleyrand was on hand (along with Fouché) to step in and ensure a smooth transition of power.

Napoleon’s return had also served as a catalyst for the diplomats in Vienna to conclude their business as soon as possible. The Final Act of the Congress of Vienna was signed on 9 June, just over a week before Waterloo. The Big Five came to an uneasy compromise over the fate of Poland and Saxony. The Tsar recognised that he had overplayed his hand and sought to turn the heat down. Russia was given part of Poland but a far smaller share than even the Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw. Prussia would receive three-fifths of the Kingdom of Saxony, the rest remaining an independent state. In addition, Prussia was given part of Poland (the Grand Duchy of Posen), Pomerania, and the Rhineland. Talleyrand thus achieved his objectives of preventing Russia from taking the whole of Poland, and Prussia from taking the whole of Saxony. Once again, he had shown himself to be Europe’s premier diplomat.

European borders established by the Congress of Vienna, 1815

In spite of his diplomatic successes at Vienna, Talleyrand knew that France would no longer have it so easy. Following the allied victory and Napoleon’s surrender, coalition soldiers occupied much of northern and eastern France. Although the Quadruple Alliance was careful to declare that their enemy was Napoleon rather than France, it was evident that the question of France’s borders was back on the table, and Talleyrand would not be at it. The Second Treaty of Paris, signed on 20 November 1815, was far more punitive than the first. France was reduced to her borders from 1790, being deprived of several territories she retained in 1814. France was also required to maintain a 150,000 strong coalition army of occupation under the Duke of Wellington which would remain in France for 5 years. (In the event, it was withdrawn in 1815).

Map of allied occupation zones in France, 1815-18

After becoming Prime Minister during the second Restoration, Talleyrand's poor relations with the King caused him to resign his office in September. He would not serve France again until 1830. Thanks to Napoleon’s opportunism and King Louis’ ineptitude, most of Talleyrand’s efforts in 1814 were in vain. Nevertheless, Talleyrand was part of a peace settlement that ensured there would be no major wars on the continent for half a century, and did all he could to limit Prussian and Russian demands to keep France secure from future hostilities. While subsequent events showed that France would not be immune from Prussian and German invasion, the prospect of German unification under Prussian leadership was far from clear in 1814-15. Talleyrand had achieved his desire for peace and ended a quarter century of war which had brought much glory for France but also a considerable amount of death and destruction. Despite of his fondness for the manners and customs of the ancien regime, he had also ensured that France would have a constitution, even if the Bourbons did not live up to his hopes.

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!