This month our blog focuses on the great French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord. Like Bernadotte, whom we covered last month, Talleyrand is a controversial figure whose name is cursed by Napoleon's followers. In this post we give an overview of Talleyrand's life and an assessment of his legacy. Next time we will have a closer look at his role at the Congress of Vienna.

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord was born in 1754 in Paris to a distinguished noble family. His father was lieutenant general in the French Army, and the young Charles Maurice would have been expected to follow in his footsteps were it not for a childhood injury that caused him to limp. From then on, he was destined for a career in the Church.

Talleyrand’s teenage years were spent at the seminary at Saint Sulpice, including a few years under the wing of his uncle at the court of the Archbishop of Reims. In spite of the tremendous wealth of the Church, Talleyrand recognised as a young man that he was not well suited to Church life. He was a keen student of Enlightenment philosophy and therefore developed a profoundly skeptical attitude towards religion in general and the Catholic Church in particular.

As he climbed the rungs of the ecclesiastical order, Talleyrand – or rather the Abbé de Perigord – became a permanent fixture of the Parisian salons, becoming close to many of the leading men and women of the age. It was around this time he developed his three main passions – wine, women, and whist.

In spite of his fondness for life in Paris, Talleyrand knew as a nobleman he could not simply remain a minor clergyman. By September 1779 he was ordained priest and served with his uncle, now Archbishop of Reims. In 1780 he became Agent General of the French Church, a position of great power and responsibility which saw him as the mediator between the King and the Church, largely over financial issues. It was the perfect training ground for a future diplomat and statesman.

After his term as Agent-General, Talleyrand expected to be given a bishopric. In the event he had to wait until the end of 1788, when he was made Bishop of Autun in Burgundy. Thus, at the age of 34 Talleyrand had joined the upper echelons of the French Church. More importantly, the well-timed appointment gave him a seat at the Estates-General as a representative of the Church (the First Estate) when it was called by King Louis XVI in 1789. Bishop Talleyrand left his See for Paris, never to return, save for one occasion several years later when his carriage broke down.

While Talleyrand was not alone as a churchman who was skeptical about religion, he was very much in the minority in his sympathy to the ideals of the French Revolution. He continued to realise how incompetent his own estate was when it had decided that it would use the opportunity to demand from a bankrupt state the cancellation of the Church’s debt. Nevertheless, unlike some of the more radical clergy such as the Abbé Sieyès, he was anxious about the prospect of the commons taking over and did not support attempts by the Third Estate (Commons) to persuade the other two to join it and form a single National Assembly. Once he saw which way the political winds were blowing, however, Talleyrand discreetly joined the Assembly.

As the National Assembly continued its deliberations amidst the storming of the Bastille and other disturbances around the country, Talleyrand broke decisively with the Church, not only supporting the abolition of the tithe but arguing in favour of the state taking over Church property in the national interest. This made him popular among the left, but he was always keen to present himself as a moderate in favour of representative government as opposed to radical mob rule. After celebrating mass for the last time on 14 July 1790, the first anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille, Talleyrand resigned his See in January 1791. Talleyrand’s moderation was viewed with skepticism by both Left and Right, who saw him as an enigmatic figure. In September 1791, just before the National Assembly broke up, Talleyrand presented an ambitious programme of public education, taking the time to criticise the existing system of education based on Church schools.

Le serment de La Fayette à la fête de la Fédération (Talleyrand is depicted to the right)

After finishing his work with the National Assembly, Talleyrand soon found himself taking on his first diplomatic assignments. In January 1792 he arrived in London in an effort to stem the descent to war. Despite his best efforts, which resulted in an initial declaration of neutrality from Pitt the Younger, political developments in France caused England to join Austria and Prussia’s war against France. The increasing radicalism of the Revolutionary Government, taken over by the Jacobins, caused the National Convention to issue an arrest warrant for Talleyrand. He was therefore compelled to remain in exile in London, where his social circle included such intellectual and political luminaries as Charles James Fox and Jeremy Bentham. His stay came to an abrupt end when Pitt ordered the expulsion of foreigners, forcing him to seek refuge in the United States and becoming a close friend of Alexander Hamilton.

Following the fall of the Jacobins in 1794, Talleyrand returned to Paris in 1795. After reacquainting himself with his old friends, most notably Madame de Staël, he was appointed foreign minister in 1797. He soon found that political power was concentrated in the five man Directory and his role was effectively reduced to that of a desk bureaucrat. Meanwhile, after defeating the Austrians in the field, the young General Napoleon Bonaparte took it upon himself to negotiate the Treaty of Campo Formio despite having no authority at all. Recognising a man who was politically ambitious and who cared very little about the Directors, Talleyrand sent Bonaparte an effusive congratulatory letter.

While serving as Foreign Minister, Talleyrand found himself embroiled in the ‘XYZ Affair,’ when representatives from President Adams of the United States were confronted with agents sent by the Foreign Minister to request bribes before opening negotiations to solve a dispute that had seen France seize American ships trading with Britain. The XYZ Affair caused the American representatives to cancel negotiations leading to the so-called Quasi-War, an undeclared naval war between France and the United States between 1798 and 1800. Incidents such as these gave Talleyrand a reputation for being notoriously corrupt, though it is a little unfair to single him out from among the corrupt officials of every stripe during the period.

Meanwhile, Talleyrand continued to ingratiate himself with Bonaparte, and the two men met for the first time in December 1797. When war with Britain recommenced in 1798, Talleyrand acquiesced to Bonaparte’s grand ambition to lead an army to conquer Egypt, and potentially destabilise British control of India. The campaigns of 1799 went badly for France, with revolutionary armies succumbing to the Austrians and Russians in Germany and Italy. Despite Bonaparte’s early success driving the Mamelukes from Egypt, he found himself bogged down in Syria confronting the combined might of the Ottoman army and the British navy. The Directory was blamed for mishandling the war effort and it seemed that France was in real danger of invasion. Talleyrand jumped off the sinking ship and resigned his ministry in July 1799.

Bonaparte realised that he was better off in France than Egypt, and duly joined the conspiracy to overthrow the Directory in the Coup of 18 Brumaire (9 November 1799). Talleyrand was an enthusiastic supporter and worked to persuade the Abbé Sieyès– the brains behind the enterprise – that General Bonaparte was the right man for the job. By 10 November the seizure of power was complete, albeit not without hiccups. Talleyrand believed that First Consul Bonaparte was the best man to restore France, and the First Consul repaid the favour by reappointing him to his former post at the Foreign Ministry.

For much of his 15 years in power as First Consul and later Emperor, Napoleon found two men indispensable – Talleyrand and Joseph Fouché, the Minister of Police. Both were men of talent and ability who were not intimidated by Napoleon. Between the years 1800 to 1807 they helped Napoleon not only to restore France’s prestige, but to make her the leading power of the European continent, and wealth and honours rained down upon both men.

It would be impossible to list all the accomplishments of Talleyrand as Napoleon’s foreign minister, so instead we will focus on particularly important events. After the Coup of Brumaire, the First Consul was keen to make peace with his enemies to allow him to turn his energies towards his domestic reform programme, which Talleyrand enthusiastically supported. In spite of Talleyrand’s position, Napoleon had entrusted negotiations with both the Austrians at Lunéville and then with the British at Amiens to his brother Joseph, and Talleyrand’s influence was limited. Nevertheless, as a former clergyman, he would play a key role in Napoleon’s efforts to make peace with the Pope, negotiating with the Papal Secretary of State Cardinal Consalvi to agree on the final text of the Concordat of 1802, which restored relations between France and the Vatican and reversed Talleyrand’s excommunication. The same year, Napoleon pressured Talleyrand to marry his longtime mistress, Catherine Grand.

Upon taking power, Napoleon had sought to reconcile disaffected Frenchmen from both left and right. Many former nobles took advantage of the amnesty offered to them by the First Consul to return to France. Napoleon’s willingness to accommodate the old order only went so far. One of the most egregious acts of Napoleon’s career took place in March 1804. Based on rather flimsy evidence that he had been involved in a conspiracy to kill him, Napoleon ordered the abduction and execution of the Duc d’Enghien, a young and popular Bourbon prince who had taken up residence a few miles beyond the border in the Grand Duchy of Baden. The circumstances surrounding the incident have been the source of considerable controversy. Talleyrand is said to have been an enthusiastic advocate for the Duke’s murder, although much of this could have been his attempts to justify the decision of his political master. When the Russians protested, Talleyrand referred not too subtly to the circumstances of the assassination of Tsar Alexander’s father, Paul, back in 1801.

Talleyrand in Jacques-Louis David's The Coronation of Napoleon

Talleyrand had hoped that the fragile Peace of Amiens between England and France would be maintained, but Napoleon refused to back down, and the two nations were once again at war by mid-1803. The glory of Napoleon’s empire reached its zenith between 1805 and 1807. Despite frequent misgivings, Talleyrand played his part by ensuring that not all of Napoleon’s major enemies on the continent – Austria, Prussia, and Russia – would be arranged against him at the same time. Thus, Napoleon was in a position to knock them out of the war sequentially, imposing punitive settlements on Austria and especially Prussia in the process. Napoleon appreciated the efforts of his Foreign Minister and in June 1806 made him the Prince of Benevento, a former papal fief in southern Italy.

By 1807, Talleyrand’s relationship with Napoleon was reaching a breaking point. He regretted Napoleon’s heavy-handed approach to Austria and Prussia. He opposed Napoleon’s efforts to establish an alliance with the Russians, whom he regarded an uncultured and semi-barbarous people. After the Russian alliance was signed at Tilsit in June 1807, Talleyrand resigned as Foreign Minister but remained within Napoleon’s inner circle as Grand Chamberlain. Under Talleyrand’s influence, Napoleon adopted a more aggressive stance towards his Spanish ally, which would culminate in a political crisis in Spain and the outbreak of the Peninsular War. When Napoleon abducted the Spanish Bourbons at Bayonne in May 1808, they were sent to Talleyrand’s château at Valençay.

The Château de Valençay

Meanwhile, Napoleon and Tsar Alexander met once more at Erfurt in the autumn of 1808 in an effort to consolidate their alliance. Napoleon had rather foolishly sent Talleyrand as his intermediary with Tsar Alexander to undermine Franco-Russian relations. The wily diplomat used this position to undermine Franco-Russian relations, charming the Tsar with the observation ‘the French people are civilised, but their sovereign is not. The sovereign of Russia is civilised, but his people are not.’ Alexander agreed to stay neutral in the imminent resumption of hostilities between France and Austria in 1809. Talleyrand had also forewarned Alexander of Napoleon’s desire to wed one of his sisters, a prospect which the Romanovs could never entertain.

During the winter of 1808-09, while Napoleon was away campaigning in Spain, Talleyrand and Fouché began to discuss the question of succession should Napoleon die in battle. The two men loathed each other and had been fierce political rivals, but both felt that Napoleon had overextended himself and threatened all of his and France’s gains. They seemed to have agreed that the successor should be a person who could be easily influenced to allow them to maintain their status and offices, and suggested Murat. When Napoleon learned of these discussions, he suspected treachery and returned to Paris in January 1809. In a public demonstration, he showered Talleyrand with a tirade of abuse, ‘you have tricked and betrayed everyone; nothing is sacred to you; you’d sell your own father,’ and blamed him for the D’Enghien Affair and the Spanish adventure. The famous description of Talleyrand as a ‘shit in a silk stocking’ appears to be a later invention.

Despite this violent tirade and demonstration of genuine anger at Talleyrand’s betrayal, the latter remained at court in the capacity of Vice Grand Elector and remained useful to the Emperor. In 1810, Talleyrand was present at a conference to discuss Napoleon’s intentions to divorce Josephine and marry a foreign princess. Always in favour of an Austrian alliance, Talleyrand suggested that Napoleon should seek the hand of an Austrian princess. The Habsburgs, having been defeated by Napoleon for the fourth time in a row in 1809, were not in a position to refuse. Thus, Napoleon took as his second wife Archduchess Marie Louise, the daughter of Emperor Francis.

During the twilight of the Napoleonic Empire, Talleyrand continued to undermine the Napoleonic project by offering intelligence to foreign agents (usually Austrians and Russians) for an appropriate price. He was opposed to Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 and could see that the writing was on the wall. After his defeat in Russia, Napoleon asked his advisors what could be done to secure peace. Talleyrand advised the only way he could end the war and save his throne was to abandon all his conquests outside France. Napoleon could not entertain such a prospect, and went down fighting in the campaigns of 1813-14. A last-ditch effort by the Emperor to reappoint Talleyrand to the Foreign Ministry was rebuffed, as the wily diplomat did not wish to go down with the sinking ship. When the allies were encroaching on Paris in the Spring of 1814 and the city seemed destined to fall to the enemy, Talleyrand took the initiative and advised the allies that the only alternative was to restore the Bourbons to the throne under Louis XVIII. By 6 April Napoleon had abdicated and agreed to go into exile in Elba.

Following the return of Louis XVIII, Talleyrand once again took up the office of Foreign Minister and was invited to the Congress of Vienna. The Congress had initially been conceived as a gathering of the victorious allies to share the spoils of their triumph over Napoleon, but Metternich saw Talleyrand as a potential Austrian ally on a number of key issues and invited him to participate as France’s representative. Talleyrand eagerly took advantage of the opportunity not only to resist attempts at partition, but to ensure that France would remain a major power in European politics, though Napoleon’s return from Elba in 1815 weakened the cause. Talleyrand’s role at the Congress of Vienna will be examined in much greater detail in our next blog post.

Talleyrand’s long record of service to successive French governments was not over after the second fall of Napoleon. After Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, he and Fouché took control of the reins of administration until the major powers – Britain, Russia, Austria, Prussia – could decide what to do. In the event King Louis was restored for a second time and Talleyrand was named Prime Minister, but soon resigned owing to his poor relations with the King. He spent the next 15 years in the role of an elder statesman, far from court but receiving a steady pension from the King.

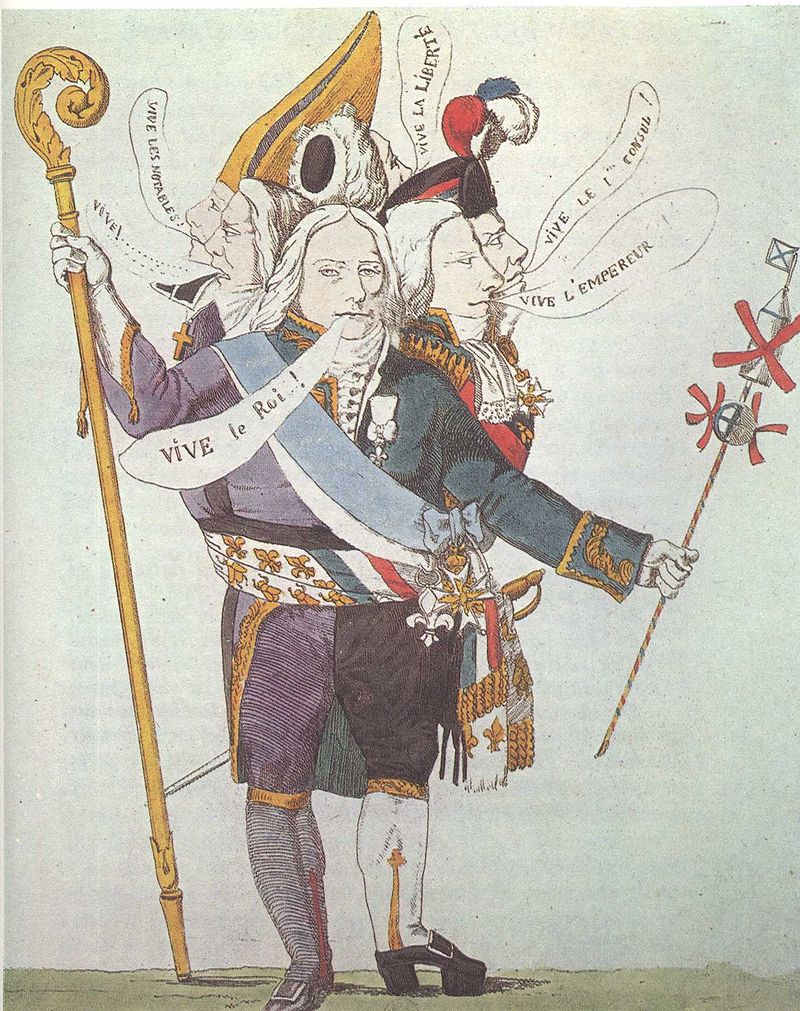

"The man with six heads" - French caricature of Talleyrand

In 1830, King Charles X was overthrown by his cousin Louis-Philippe of Orleans in the July Revolution. The new King Louis-Philippe appointed Talleyrand as Ambassador to London. Already an old man at the age of 76, Talleyrand reluctantly accepted the appointment. During his four year stint as ambassador, he helped to effect a rapprochement between England and France, fostering the era of cordial relations between the two traditional rivals that continues to the present day. The embassy in London was Talleyrand’s final service to France. He retired in 1834 and died in 1838 at the age of 84 at his château at Valençay.

Talleyrand’s reputation among both historians and the wider public is mixed. While regarded as a brilliant politician and diplomat, and above all a great political survivor, his name is often associated with treachery and corruption. This is a little unfair. Talleyrand might have been more corrupt than others, but it was common at the time for the wheels of diplomacy to require a fair amount of pecuniary grease. As for his treachery, Talleyrand may have betrayed individuals but he rarely betrayed principles. He was a moderate and pragmatic politician who was comfortable serving governments of different persuasions. He had his own idea of France and her place in Europe, and used his considerable talents to steer events in that direction, even if it meant working against his political master at the time. Talleyrand desired for France a liberal constitutional polity which maintained peaceful relations with her neighbours. By the end of his life, much of this had been achieved.

Are you a fan of Talleyrand? Take a look at our Talleyrand matryoshka mug!

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!