One of the Tsar’s palatial halls is an apartment

With neither gold nor velvet rich; here no assortment

Of coronation gems, kept under glass, is found;

But up and down, throughout its length and all around,

His ranging brush instinct with free and generous feeling,

An artist has embellished it from floor to ceiling.

No maidenly madonnas, nymphs on sylvan lawns,

Full-bosomed women, goblet-wielding fauns,

No dances, hunting scenes – instead, all cloaks and sabres,

And countenances marked by war’s resolve, war’s labours.

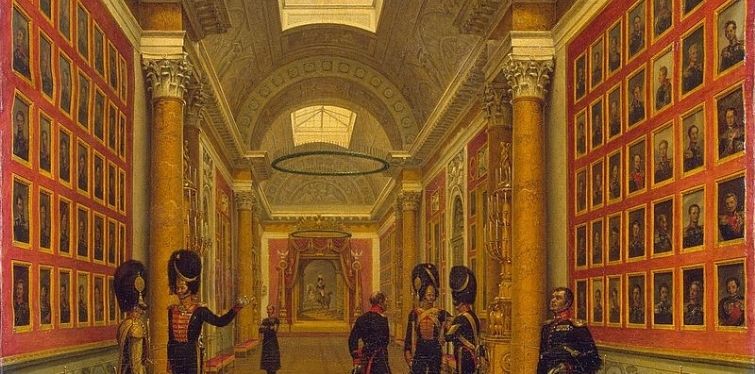

Thus Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s greatest poet, begins his poem The Commander, honouring Field Marshal Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, one of Russia’s greatest heroes of the Napoleonic invasion of Russia. The “palatial hall” that Pushkin so vividly describes is the Military Gallery of 1812 in St Petersburg’s Winter Palace. Sandwiched in a long and narrow corridor between the Armorial Hall and St George’s Hall, two of the largest rooms in the palace, the Military Gallery is nevertheless one of the most impressive sights in the whole Hermitage complex.

It was Tsar Alexander I (1801-25)’s idea to create a gallery in the Winter Palace dedicated to the generals who had distinguished themselves during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia between 1812 and 1815. In 1819 the Russian Tsar commissioned the British artist George Dawe to paint the portraits of the Russian generals who would adorn the walls of his new gallery. Over the next ten years, Dawe, ably supported by his assistants Wilhelm August Golicke and Alexander Polyakov, painted 332 portraits to hang in the gallery. Most of the portraits were painted from life, while the portraits of already deceased generals were copied from existing portraits. There were no portraits found of thirteen of the deceased generals, leaving empty spaces with their names inscribed on the frames.

Tsar Alexander died unexpectedly in 1825 and was succeeded by his brother Nicholas I (1825-55). The following year, the Gallery was built on a north-south axis between the Armorial Hall and St George’s Hall to the design of Carlo Rossi, an Italian neoclassical architect who was responsible for many of St Petersburg’s public buildings during this period. The Gallery replaced several small rooms which previously occupied the space. Nicholas presided over the inauguration ceremony of the 1812 Gallery, its long walls covered by five rows of bust-length portraits of generals clad in their uniforms. The ceremony took place on 25 December 1826, exactly fourteen years since the official end of the Napoleonic invasion of Russia.

In 1828-29, after the official opening, Dawe painted four full-length portraits featuring the most prominent officers in the Russian Army. A visitor who enters from the Armorial Hall encounters the grey-haired figure of Field Marshal Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov to the left of the doorway. Kutuzov served as the supreme commander of the Russian Army between August 1812 and his death in May 1813 and was responsible for the decision to abandon Moscow to Napoleon. He is shown standing under the shade of a tree with his right hand outstretched, perhaps giving an order to pursue the retreating Napoleonic army.

On the other side of the doorway on the right stands Field Marshal Mikhail Barclay de Tolly. A Baltic German with Scottish heritage, Barclay de Tolly had been Minister of War and de facto commander-in-chief of the first half of the 1812 campaign. The strategic retreat of the Russian Army under Barclay’s leadership made him extremely unpopular and he was superseded in command by Kutuzov on the eve of the climactic Battle of Borodino. He withdrew from the army in the winter of 1812 but returned the following year to assume the supreme command in June 1813. Barclay remained at the head of the Russian Army when it marched in triumph through the gates of Paris in March 1814 alongside its Austrian and Prussian allies. Dawe’s portrait shows him standing in front of a battle scene – most likely the Battle of Montmartre which led to the capture of Paris. This was the portrait which inspired Pushkin’s poem, which celebrated Barclay as a commander whose strategic insight in 1812 was unappreciated by wider Russian society.

The stern figure of Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich stands opposite that of Field Marshal Kutuzov. The younger brother of Tsar Alexander, Constantine served as commander of the Guards Corps, though his insubordination and frustration with Barclay’s leadership during the early stages of the 1812 campaign caused him to be sent back to St Petersburg on two occasions. Although Constantine served with some distinction as commander of the Guards in 1813-15, the honour of a full-length portrait was granted to him as a member of the imperial family rather than his military talents.

Constantine’s inclusion might be undeserved but is not entirely unexpected. The fourth member of this quartet, his portrait opposite that of Barclay, is the most surprising. British visitors would easily recognise the Duke of Wellington wearing the iconic red uniform of the British Army. So how did Britain’s greatest general find himself among all these Russian generals? In 1815, in recognition of the Allied victory at the Battle of Waterloo, Tsar Alexander made Wellington a Field Marshal in the Imperial Russian Army. The portrait was most likely painted during Wellington's visit to St Petersburg in 1826 for the funeral of Tsar Alexander I.

Wellington is not the only foreigner to feature on the walls of the 1812 Gallery. In addition to the four full-length portraits, there are three equestrian portraits featuring the sovereigns of Russia, Prussia, and Austria. Tsar Alexander’s portrait appears at the southern end of the gallery under a canopy. A portrait of Alexander on horseback painted by Dawe had initially occupied the space, but it was replaced a few years later by one painted by the Berlin artist Franz Kruger. Kruger was also responsible for the painting of King Frederick William III of Prussia. The remaining equestrian portrait, that of Emperor Francis I of Austria, was painted by the Viennese artist Johann Peter Krafft. Thus, Russia’s allies are represented in the Gallery by the sovereigns of Prussia and Austria, and the commander-in-chief of the British Army.

While the portraits of the sovereigns and field marshals are especially prominent in the Military Gallery of the Winter Palace, among the bust-length portraits there are many generals whose names continue to live on in Russian historical memory. Pyotr Bagration, Dmitry Dokhturov, Nikolay Raevsky, Matvei Platov, Denis Davydov are just a few of those who made prominent contributions to Russia’s victory over Napoleon. In addition, there are no less than six men who would become Field Marshals: Prince Fabien von Osten-Sacken, Prince Pyotr Wittgenstein, Prince Ivan Paskevich, Count Hans Karl von Diebitsch, Prince Pyotr Volkonsky, and Prince Mikhail Vorontsov.

A terrible fire in 1837 destroyed large parts of the Winter Palace, including the 1812 Gallery. Thankfully, all of the portraits were saved from the flames by the Palace Grenadiers, a unit of veterans of the Napoleonic Wars established by Nicholas I in 1827 to guard the Winter Palace. The gallery was rebuilt by Vasily Stasov to Rossi’s original design. With the exception of a couple of paintings by Peter von Hess depicting battle scenes from the 1812 campaign, which were transferred to the room during the Soviet period, the Gallery has remained effectively unchanged since the late 1830s. The Winter Palace and Hermitage Museum complex is full of wonderful treasures from all over the world, but Napoleonic history enthusiasts are well advised to spend a few minutes among this gallery of Russian heroes.

We hope you enjoyed this blog post. If you are interested in buying some artwork inspired by the paintings in the Military Gallery of 1812, please see below.

Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov Art Print

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!