This is the third part of a blog series looking into the experience of Poland during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Last time we covered the Polish patriots in exile who sought to free their country under the standard of Republican France. This post will cover another project to restore Polish statehood, this time from within the Russian Empire.

When Tsar Paul succeeded his mother Catherine the Great in 1796, he began to reverse many of her policies. He recognised that Poland had been treated harshly during the partitions. Less than two weeks after his mother’s death, Paul released Kościuszko from prison and promised to free all Polish prisoners in Russia. He invited the deposed King Stanislaw Augustus to St Petersburg and accommodated him in the luxurious Marble Palace. While Stanislaw was effectively under house arrest, he was treated as a fellow monarch by the Tsar. However, Paul had told Kościuszko and Stanislaw that while he regretted the partitions, nothing could be done to reverse them.

Tsar Paul I of Russia

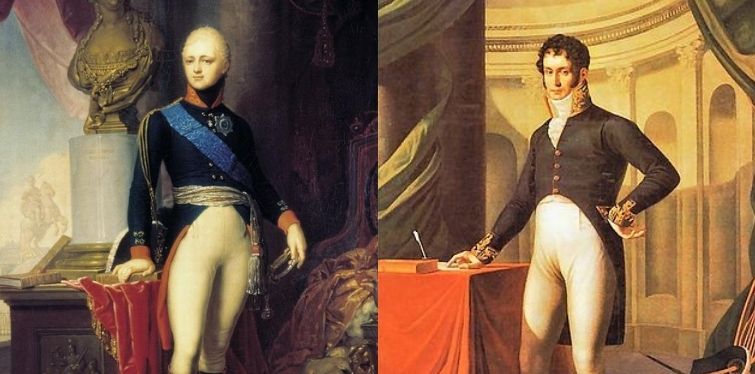

Paul’s ill-fated reign ended in March 1801 when he was killed in a palace coup. His son and successor Alexander I was also keen to redress past wrongs and to restore Polish statehood in one form or another. Back in 1795, two young Polish princes arrived in Petersburg as political hostages following the Third Partition. Hailing from the illustrious Czartoryski family, they were given appointments at Court and became officers in the Guards regiments. The elder, Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, developed a close friendship with Alexander. Both men had a classical upbringing and shared a broadly liberal outlook. During a meeting in 1796, Alexander confided to Czartoryski his opposition to his grandmother’s policy and that he had privately wished for the success of the Kościuszko rebellion. He also expressed sympathy for the ideals of the French Revolution, while condemning the excesses of the Terror.

Stunned by this admission and honoured to be in the confidence of the future Tsar, Czartoryski was optimistic about the prospect that his homeland might soon be restored. Alexander’s youthful idealism was such he often held more radical beliefs than his Polish friend. When he criticised the principle of hereditary monarchy, Czartoryski was quick to remind him how an elective monarchy had contributed to Poland’s demise. He sought to dissuade Alexander from any thoughts of renouncing his right to inherit the Russian throne. When Paul became Tsar of Russia, Czartoryski was appointed Alexander’s aide-de-camp.

As much of a Polish patriot as the likes of Kościuszko and Dąbrowski, Czartoryski sympathised with the cause of the Polish legions in Italy under Bonaparte’s command, and hoped their designs would be fulfilled. When Russia joined the Second Coalition in 1798, Czartoryski was viewed with suspicion in the Russian court. He was given a diplomatic assignment to Italy and did not return until after Paul’s assassination, whereupon he was immediately recalled to St Petersburg.

Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski

Not long after his return to Russia, Czartoryski found himself in a position of influence as a member of Alexander’s ‘Unofficial Committee’, a group of the Tsar’s young friends who met with him regularly and presented him with proposals on a number of issues close to his heart, including idealistic projects to emancipate the serfs and establish a constitutional government. The other members of this group were Pavel Stroganov, Nikolai Novosiltsev, and Viktor Kochubey. While the others were given formal appointments at court and in the civil service, Czartoryski was more concerned about the fate of Poland and did not initially accept any office.

Czartoryski prevailed upon Alexander to free any remaining Polish prisoners in Siberia and restore to them their confiscated estates. When Alexander reformed the Russian ministries in 1802, Czartoryski was persuaded to accept the post of Assistant Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was more enthusiastic about his appointment as administrator of the educational district of Vilna, which gave him responsibility over all the schools in the eight Polish (in effect Lithuanian) provinces of the Russian Empire. He was also given the post of Curator of the University of Vilna, one of the more progressive educational establishments in the empire. The educational reforms Czartoryski introduced, which were uniform across the Polish provinces, were regarded as a model for educational reform throughout the empire.

Czartoryski had accepted his appointment as Assistant Minister of Foreign Affairs on the condition that he would not be party to any harm caused to Poland. As a result of his appointment, he was in a position to familiarise himself with the diplomatic correspondence of the courts of Europe. He worked closely with Foreign Minister Alexander Vorontsov, whose policy was to maintain peaceful relations with the rest of Europe, allowing the Tsar to focus on internal reforms. The fact that a Pole occupied such a senior position in the Foreign Ministry caused disquiet among many Russian nobles. Knowing that the Poles were sympathetic towards France, they believed Czartoryski was acting in the interests of Bonapartist France.

Alexander Vorontsov

The year 1804 proved a pivotal one for Russian policy in Poland. Czartoryski had taken the reins at the Foreign Ministry from the ailing Vorontsov. While the arrangement was supposed to be temporary, Czartoryski’s began to pursue a more active foreign policy. He saw an opportunity to use his office to improve the fate of his native Poland, while being conscious of his duty to serve the interests of the Tsar and his subjects. He pursued a policy aimed at reversing historical injustices in Europe. He referred specifically to the Greeks and Slavs in the Ottoman Empire, but also sought to apply the principle to Poland.

Czartoryski believed that any understanding between Alexander’s Russia and Napoleon’s France would necessarily be at the expense of Poland. He also believed that it was impossible. He later wrote in his memoirs, “Napoleon could not suffer any rivals in the career upon which he had entered. All the attempts which were made to act on an equal footing with him failed. His ally had either to carry out his plans or become his enemy.” Czartoryski therefore developed his foreign policy on the assumption that there would soon be a rupture between Russia and France.

The anticipated rupture came in March 1804 with the kidnap and execution of the Duc d’Enghien, a young Bourbon prince who had been in exile near the French border. Czartoryski wrote a memorandum denouncing the act as a violation of international law, and proposed breaking off diplomatic relations with France. He also advised diplomatic overtures to be made to potential allies in case of war.

Nikolai Novosiltsev

In 1804 Nikolai Novosiltsev was entrusted with a mission to London to negotiate a treaty of alliance with William Pitt’s government. Novosiltsev was entrusted with secret instructions in the name of the Tsar drafted by Czartoryski. This justified a coalition against France on the basis that the French government was acting tyrannically under Napoleon, and denying its subjects the liberties and freedoms promised by the Revolution. The instructions suggested that Piedmont, Holland, and Switzerland should be restored and the liberties of their peoples guaranteed by England and France. In the event of the overthrow of Napoleon, the Tsar left open who should be King of France. Novosiltsev was also instructed to obtain from the British government a couple of concessions: namely the cession of the island of Malta, and an end to the British practice of searching and detaining neutral shipping.

A memorandum drawn up by Czartoryski outlined the plan for European peace in the event of a successful war against France. France would have her ‘natural borders’ up to the Alps and the Rhine. The German principalities will be reorganised into a federal empire excluding Austria and Prussia. Poland would be restored with all her territories from the First Partition. The Emperor of Russia would take the title of King of Poland in personal union. Austria and Prussia would be compensated by territories in Germany and Italy. The fate of the Ottoman Empire would depend on whether she supported France in the subsequent war. It was hoped that this reorganisation of Europe would help to establish a general European peace under the aegis of England and Russia.

By such means, Czartoryski had successfully reconciled the interests of the Russian Empire and his own desires for the restoration of Poland, which the Tsar shared. However, Novosiltsev was unable to come to an agreement with the British that met Russian negotiating objectives. While Pitt agreed with the general principles behind the Russian proposal, Britain could never consent to the evacuation of Malta, nor to the changes in the maritime code that Russia had sought. While Treaty of Alliance was signed in April 1805, it was not ratified until July with the outstanding issues unresolved. By then Austria, which had earlier entered into an alliance with Russia, was preparing for military action in Germany and Italy.

With Prussia remaining neutral, Tsar Alexander considered leading two corps through Prussia on the way to the anticipated theatre of hostilities in southern Germany, pre-emptively declaring himself King of Poland in the process. Alexander, with Czartoryski in his suite, stopped off at the Czartoryski estate at Puławy, where Prince Adam’s parents lived. Prince Jozef Poniatowski was informed in advance of the plan and gathered a body of soldiers at Puławy to lead a national uprising as the Russians crossed the border. While the diplomatic consequences of such a move where considered, I Corps of Napoleon’s Grande Armée had passed through Prussian territory without authorisation. In response, the King of Prussia gave Russian troops free passage through his territories. Tsar Alexander and King Frederick William swore eternal friendship on the grave of Frederick the Great and concluded a treaty of alliance on 3 November.

King Frederick William III, Queen Louise, Tsar Alexander I at Frederick the Great's tomb

The new Russo-Prussian agreement undermined Czartoryski’s plans for Poland. He accompanied the Tsar on the journey to the Russian camp near the city of Brünn. The Austro-Russian army’s defeat at Austerlitz on 2 December led to Austria’s withdrawal from the coalition. Prussia also abandoned its alliance with Russia and returned to its policy of neutrality. While urging the need for a defensive alliance with Prussia, Czartoryski criticised the Tsar’s inclination for a close alliance with Prussia. In a letter from April 1806, he criticised the Tsar’s conduct in the autumn of 1805 prior to the Battle of Austerlitz.

Czartoryski had lost faith in the Tsar and his policy. He had accepted his ministerial position on the condition that he would do no harm to Poland, and recent developments indicated that this condition could no longer be met. In March 1806, he sent a letter to the Tsar asking to be relieved of his duties as Foreign Minister. This request was repeated on several occasions before the Pole was finally allowed to relinquish his post in June 1806. He was replaced by Baron Andreas von Budberg, one of the Tsar’s former tutors. Czartoryski continued to enjoy the confidence of the Tsar as a member of the Unofficial Committee. In December 1806, with Napoleon’s Grande Armée marching through Poland following victory over the Prussians at Jena-Auerstedt, Czartoryski urged the Tsar to support a Polish uprising against Napoleon.

Alexander rejected the proposal as unrealistic. Thus, Napoleon rather than Alexander who would once again take up the cause of Polish nationhood as a means to furthering his geopolitical objectives.

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!