This is Part 3 of a three part series presenting a narrative of the course of Napoleon's 1812 campaign, covering the retreat of Napoleon's army following the Battle of Maloyaroslavets until its eventual destruction at the Berezina. Check out Part 1, Part 2, and our existing blog posts on the topic of Napoleon's invasion of Russia.

The morning after the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, Napoleon and his staff inspected the battlefield, littered with the bodies of dead and wounded of both armies. While Napoleon was lamenting the terrible loss of life, the imperial entourage was surprised by a body of Cossacks, and the Emperor and his marshals were forced to engage in hand-to-hand combat before escaping. After this close shave Napoleon ordered his doctor to make him a phial of poison. He had no intention of being taken alive by the notorious Cossacks.

By now Napoleon and what was left of the Grande Armée was in full retreat, seeking to return to Smolensk as soon as possible. He still believed that he could salvage something from his campaign by joining up with Marshal Victor’s IX Corps in Smolensk and establishing winter quarters there. The Emperor would return to Paris and raise a new army to take to the field the following spring and restart the campaign. Yet the Grande Armée was in a sorry state, and things would go from bad to worse for Napoleon and his men over the course of the winter.

The Grande Armée’s supplies were dwindling at a rapid rate and the men were often forced to feed on whatever horses they had left. The lack of horses meant that Napoleon was essentially ‘blind’ to the whereabouts of the enemy. Kutuzov proceeded cautiously with his main army, but Napoleon’s men were often subject to surprise raids by partisans and Cossacks. While small raiding parties could never do great damage, the need to be on alert at all times exhausted the soldiers and had a great psychological effect. This psychological effect would only have been heightened on 29 October, when the Grande Armée rejoined the Smolensk Road and retreated past the Borodino battlefield, still littered with corpses of friend and foe alike.

Keen to return to Smolensk at soon as possible, the Grande Armée was strung out over a distance of around 50 kilometres, making it vulnerable to Kutuzov’s army. Kutuzov chose to take parallel roads where supplies were more plentiful but progress was slower. Nevertheless, on 3 November, General Miloradovich’s vanguard caught up with Davout’s rearguard at Vyazma. While the Russian general failed to surround Davout’s corps and cut him off from the rest of the army, Miloradovich managed to capture a large number of prisoners as the Russian army registered a morale-boosting victory.

While the first snows had begun to fall just after Napoleon left Moscow, the temperature had seriously plummeted by 6 November. Although not excessively cold by the standards of a Russian November, the certainly had a significant impact on the hungry and exhausted French army. Napoleon had never intended to fight a winter campaign and thus the army was poorly equipped for the freezing temperatures. While the Russian army also suffered from the cold, better equipment and supply, together with the familiarity with cold winter temperatures, meant that they did not suffer as much as the Grande Armée.

Napoleon and his men soon found some brief respite, arriving at Smolensk on 9 November. Napoleon himself stayed in the city for five days as his men made use of whatever supplies they could find. This delay, however necessary, allowed Kutuzov to overtake Napoleon and outflank him to the southwest. Without his cavalry force, Napoleon had no idea where Kutuzov was. While his subordinates tried to persuade him to block Napoleon’s retreat and force him to fight his way through, Kutuzov was content to preserve his own force and allow the elements to destroy the enemy.

Napoleon chose to send his corps out of Smolensk by one day intervals, which would have made them extremely vulnerable to any attempt by Kutuzov to attack in force. The Russian commander was content to allow Napoleon’s Old Guard pass, but by 15 November, the Russians began to take more active measures, with Miloradovich harassing Eugene and Davout’s corps, inflicting significant losses and capturing their artillery and baggage trains. Davout’s hat and baton which were part of this haul are now on display in the Museum of the Patriotic War of 1812 in Moscow. By 17 November Miloradovich’s men had blocked the road, with Marshal Ney’s rearguard still in Smolensk. Abandoned to its fate, Ney’s men made several courageous attempts to break through but were repulsed. Through his daring and inspirational leadership, Ney and 800 men managed to take an alternative route through the woods and rejoin Napoleon, and shortly thereafter to berate the Emperor for abandoning him. While Ney’s feat caused Napoleon to call him the ‘bravest of the brave,’ Krasny was a disaster for the French, who lost 10,000 men killed and a further 20,000 captured.

While Napoleon’s main army was retreating from Moscow, two Russian armies were advancing on the northern and southern flanks. Between 18 and 20 October, Wittgenstein’s corps, bolstered by Fabian von Steinhel’s corps of 30,000 men and effectively an army in its own right, defeated St-Cyr at the Second Battle of Polotsk. Seeing his northern flank collapsing, Napoleon had ordered Victor’s IX Corps to leave Smolensk and retake Polotsk. It was too little too late, and Wittgenstein’s army would prove its superiority. Despite joining his forces with elements of Oudinot’s II Corps and St-Cyr’s VI Corps, Victor was defeated at Chashniki on 31 October and at Smoliani on 14 November. He was now retreating towards Napoleon’s main army, with Wittgenstein following behind.

While Wittgenstein pushed forward in the north, Admiral Pavel Chichagov’s Army of the Danube had been making its way from the Balkans to join with Tormassov’s Third Army by mid-September, and thence to press forward against the outnumbered Saxons and Austrians defending Napoleon’s southern flank. After detaching almost half his army under General Fabian von der Osten Sacken to pursue the retreating Saxons and Austrians, Chichagov and his remaining 33,000 men turned their attention towards cutting off Napoleon’s retreat. Chichagov moved swiftly into Belorussia and captured Minsk by mid-November, with the view of cutting off Napoleon at the River Berezina. With three Russian armies converging from different directions, Napoleon risked being surrounded and being the victim of the sort of strategic manoeuvre that was his signature. Confident of capturing Napoleon, Chichagov issued the following proclamation:

‘Napoleon’s army is in flight. The person who is the cause of all Europe’s miseries is in its ranks. We are across his line of retreat. It may easily be that it will please the Almighty to end his punishment of the human race by delivering him to us. For that reason I want this man’s features to be known to everyone: he is small in height, stocky, pale, with a short and fat neck, a big head and black hair. To avoid any uncertainty, catch and deliver to me all undersized prisoners. I say nothing about rewards for this particular prisoner. The well-known generosity of our monarch guarantees them.’

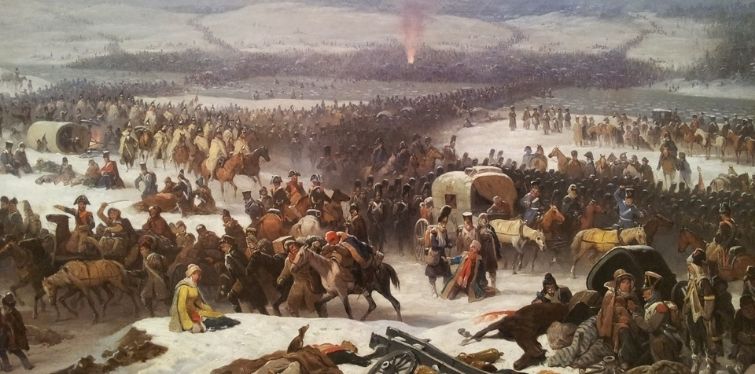

The fate of Napoleon and his army would thus be decided on the banks of the River Berezina, some 70 kilometres east of Minsk. An unexpected thaw near the end of November caused the ice to break. The movements of the three Russian armies converging on the Berezina were not well co-ordinated. Chichagov had been the first to arrive, and had crossed over into the town of Borisov on the eastern bank. His vanguard was driven back by the enemy vanguard commanded by Oudinot. Crucially, Chichagov managed to destroy the bridge at Borisov, but with Wittgenstein and Kutuzov still some distance away, the admiral was vulnerable to Napoleon’s full force. Chichagov was concerned that Napoleon would turn south and threaten his rear in Minsk and duly moved most of his force southwards. Napoleon ordered his pontooniers to give the impression they were building a bridge at Borisov, distracting Chichagov while ordering a group of Dutch pontooniers to build a bridge at Studenka, seven miles to the north. By the time Chichagov realised what was happening, Napoleon was already able to withdraw much of his viable force. Nevertheless, his rearguard commanded by Victor suffered heavy casualties thanks to Wittgenstein’s artillery. Meanwhile Kutuzov’s vanguard had just arrived on the scene. The bridge at Studenka was burned too early, and 30,000 stragglers were left on the eastern bank. Napoleon’s force was down to 25,000 men, but he and his senior commanders had escaped.

Chichagov is often blamed for his conduct at the Berezina and for allowing Napoleon to escape. While it is true that he had allowed himself to be hoodwinked by Napoleon, both Wittgenstein and Kutuzov in particular were also to blame for their slowness in coming to his aid. While Kutuzov was right to be concerned about the condition of his army, and recognised that Chichagov’s men were both fresher and more experienced (through their service against the Turks), the chances are that Kutuzov intended for Napoleon to escape. Indeed, he had said as much after the Battle of Maloyaroslavets to Robert Wilson, the British liaison officer, “I am by no means sure that the total destruction of the Emperor Napoleon and his army would be of such benefit to the world; his succession would not fall to Russia or any other continental power, but to that which commands the sea, and whose domination would then be intolerable.” Kutuzov’s words would prove prophetic as the Russians were subject to another French invasion in 1854, this time allied with the British, the dominant naval power.

The Berezina was the final major engagement of the 1812 campaign. Napoleon had broken through and the prospect of a Russian Cossack detachment running into him was extremely remote. The army that managed to get across the Berezina continued to disintegrate in December, and on 5 December Napoleon left for Paris, leaving Murat in charge of what was left. On 14 December, Michel Ney crossed the Niemen with his rearguard, and the marshal himself was said to have been the last man to leave Russia. Napoleon had crossed the Niemen six months earlier with 500,000 men, only 20,000 of whom would return to the ranks. Up to half, if not more, had perished in Russia. The Russian armies had suffered much during the campaign, with almost half their number in hospital from wounds or disease. Kutuzov resisted Tsar Alexander’s exhortations to move faster, and most of the men would recover to fight Napoleon’s armies in Germany in 1813.

We hope you enjoyed this blog post. If you’re interested in buying some products featuring Russian generals of 1812, please check out our Russian collection!

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!