This blog post is the first of a five part series on Napoleon’s great battles. We are choosing to apply a broad definition of ‘great’ – some battles are great in size, others in their political influence, or in demonstrations of Napoleon’s greatness as a military commander. To check out the rest of the series, click here. We look first at the Battle of Marengo on 14 June 1800, where Napoleon's army snatched victory from the jaws of defeat and enabled Napoleon to consolidate his position as First Consul.

Napoleon Bonaparte had seized power in the Coup of 18 Brumaire in November 1799, and established himself as the First Consul of the Republic. Since the Revolution of 1789, French domestic politics had been in constant turmoil with several changes in government. These were often accompanied by a significant amount of blood spilt. General Bonaparte hoped that he could restore political stability to Paris, which was by no means guaranteed. In order to consolidate his political power, he recognised he had to make an advantageous peace with the Second Coalition. To do that, he would have to return to Italy.

During Bonaparte’s First Italian Campaign in 1796-97, he had made his name by defeating Piedmontese and Austrian forces in Northern Italy with a small army of no more than 30,000 men. This allowed him to negotiate the Treaty of Campo Formio with the Austrians, bringing Northern Italy into the French Republic’s sphere of influence by establishing the Cisalpine Republic. By 1798, Austria and France were once again at war over Northern Italy. While Bonaparte was on his Egyptian campaign, in 1799 an Austro-Russian army under the command of the brilliant Russian Field Marshal Alexander Suvorov swept aside several French Revolutionary armies and dissolved the Cisalpine Republic. These setbacks contributed in part to the unpopularity of the Directory (the French government), which prompted Bonaparte to abandon his army in Egypt to return to France and take power.

By the time Napoleon had taken power as First Consul, the Russian threat had already been nullified. After his success in Italy, Suvorov had been planning to march on Paris. Suvorov’s Austrian allies, jealous of his success, abandoned him and the Russian was forced to march across the Alps into Switzerland to support General Koraskov’s army at Zurich. By the time Suvorov had made it over the Alps, Korsakov had already been defeated by General Andre Massena. Tsar Paul of Russia, incensed by Austrian perfidy, withdrew from the Second Coalition in early 1800. This was good news for France, but the Austrians retained their hold of Northern Italy and were advancing on Genoa, the last French stronghold in Italy. First Consul Bonaparte was determined to win it back from the Austrians.

After the Russians departed, the 120,000-strong Austrian army in Italy was under the command of Michael von Melas, previously subordinate to Suvorov. The 71-year old Melas was like many Austrian commanders of the time, competent and principled but not particularly innovative. After taking considerable time to consolidate his position, by early April the Austrians had surrounded the garrison at Genoa, under the command of General Massena. Napoleon gathered his Army of Reserve in Switzerland, with Chief of Staff General Louis-Alexandre Berthier in command. Napoleon gave express orders for Massena to hold on and wait for his relief force. For two months, Massena fought a number of desperate actions, inflicting heavy casualties on the Austrians but with his own force increasingly dwindling.

Napoleon left Paris on 6 May. With time of the essence, the First Consul decided to take the shortest route to Genoa – via the formidable Great St Bernard Pass. This also brought with it the element of surprise, since the Austrians could not have expected Napoleon to lead his army this way. On 15 May the French vanguard under General Jean Lannes began the famous crossing. The pass was still covered in snow, and artillery pieces were dragged up with the greatest difficulty. The First Consul crossed on the 20th, depicted famously if not particularly accurately by Jacques-Louis David. Even though Massena’s men in Genoa were suffering terribly with dwindling supplies and a typhus outbreak, Napoleon chose to head to Milan to secure his communications, taking the lightly-defended city on 2 June. Massena surrendered Genoa on 4 June, evacuating his men by sea. This freed up General Peter Ott’s force which had been besieging the city.

Napoleon Crossing the Alps, Jacques Louis David (Public Domain)

Despite Bonaparte’s arrival, the Austrians continued to outnumber the French in Italy. Nevertheless, Melas was convinced that Napoleon’s army was considerably larger than it actually was. He recalled Ott, intending to launch a counteroffensive by concentrating his forces in Alessandria, some 50 miles to the southeast of Turin. On 9 June, Ott was defeated by General Lannes at Montebello. While this did not prevent him from joining with Melas, the defeat further sapped the morale of the Austrian army and its high command, who felt as though Bonaparte was running rings around them.

Even with Ott’s arrival, Melas had little more than 30,000 men at his disposal in Alessandria. Almost 50,000 Austrian troops were tied up in garrison duty in more than a dozen fortresses. Even so, Melas enjoyed narrow numerical superiority over Napoleon’s 28,000 men, having sent off 20,000 men in various detachments to keep an eye on Austrian forces elsewhere. He was advancing towards Alessandria from the southeast. Effective Austrian cavalry screens meant that Napoleon lacked intelligence about Melas’s whereabouts and his intentions, though he believed there was a chance that Melas would attempt to escape to Genoa. To cover this, he sent 6,000 men south under the command of General Louis Desaix, who had arrived from Egypt on 11 June. This left Bonaparte with only 22,000 men to face Melas.

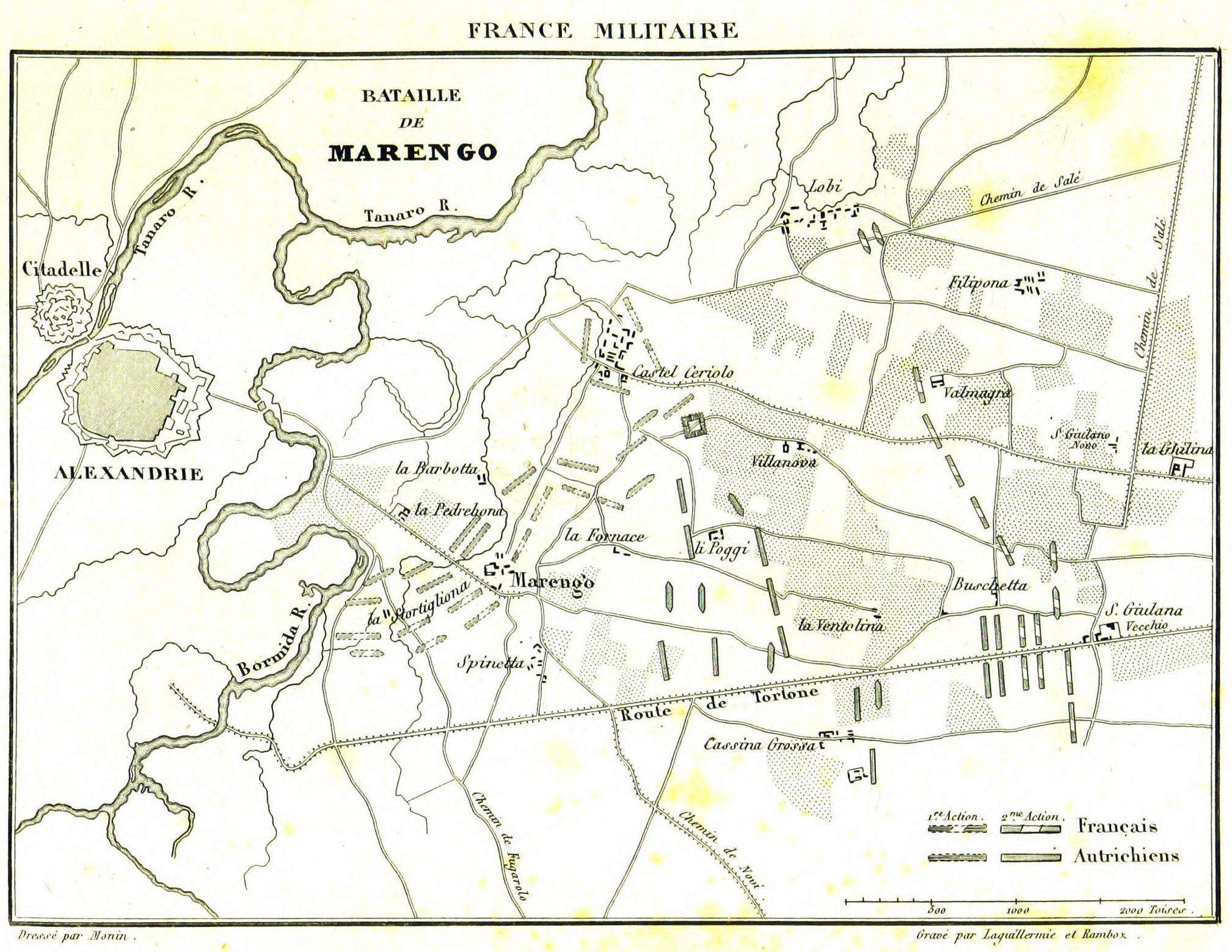

Having been outwitted by Napoleon’s manoeuvres and misinformation, Melas believed he was at risk of being surrounded in Alessandria by a far larger army. He therefore resolved to fight his way out eastwards before Napoleon could get into position. On the evening of 13 June, he ordered 3,000 men under General Andreas O’Reilly over the Bormida River to establish an advanced position. O’Reilly was forced to fall back against General Claude Victor, who stopped the pursuit at Marengo, some 3 kilometres to the southeast of Alessandria.

Battle of Marengo Map (Wikimedia Commons)

The Austrian attack began on the morning of 14 June as Melas’s men crossed the Bormida towards the French position at Marengo. The plan was straightforward. With the majority of his forces, Melas would launch a frontal assault against Napoleon’s army. Meanwhile, a smaller force under Ott in the north would operate against the French right. Although Napoleon was keen to bring the Austrians to battle, he did not anticipate that Melas would be the aggressor. Unprepared for battle, Napoleon and Berthier were surprised to see large numbers of Austrians heading towards Marengo at 8 o’clock. General Victor rushed to secure his left flank while calling for reinforcements. By 10 o’clock he was joined by Lannes and Murat’s reserve cavalry.

Although the Austrians found it difficult to progress over the Fortanone brook in front of Marengo. General Haddick, leading the assault, was mortally wounded, and his replacement General Bellegarde would also have to leave the field. Meanwhile, Ott’s column advanced on Castel Ceriolo to the northeast of Marengo. He then turned to attack Lannes’ flank, forcing the French general to move away men defending the line at Marengo. Melas was unaware of Ott’s success in the north and decided to attempt to outflank the French from the south. The cavalry force he sent to ford the Fontanone was charged by General Kellermann’s cavalry, foiling the attempt.

Nevertheless, the pressure on the French position from both Austrian columns was beginning to bear. Napoleon rushed to secure his right flank against Ott and at noon sent word to recall Desaix. The French units around Marengo began to be overwhelmed by Austrian numbers. Napoleon saw that the situation was desperate on the northern flank and called up his reserve, the Consular Guard, from his headquarters at San Giuliano. After the Austrian infantry drove off Murat’s cavalry, it engaged in a firefight with the Guard. With Lannes’ men falling back, the Consular Guard was isolated and charged in the rear by Colonel Johann Frimont’s cavalry force. Napoleon mobilised General Bessieres’ Guard cavalry in an attempt to rescue the grenadiers of the Guard, but Bessieres encountered fierce resistance from Austrian musketry and pulled back.

By around 4:30 in the afternoon, the French army began a general withdrawal to the east in some disorder. The septuagenarian Melas, convinced he had already won the battle, handed over overall command to Lieutenant Field Marshal Konrad von Kaim and returned to Alessandria to write his battle report. Melas’s Chief of Staff, Anton von Zach, led the pursuit of the French army. With his army in full retreat, and facing a column of Austrians in pursuit, Napoleon was gratified to see Desaix return at 5pm. The First Consul turned to his friend and asked him for his assessment of the situation. Desaix replied, “The battle is completely lost. But there is time to win another.”

Desaix quickly conceived of a plan to win the new battle. A battery of 16 guns under General Auguste Marmont and three battalions of the 9th Light Infantry regiment were sent forward to hold back the Austrian column, which Zach had rushed forward along the road to San Giuliano. Under artillery and light infantry fire, the Austrian infantry had difficulty forming into line. Marmont’s guns caused confusion among the Austrian ranks. At around 5:45, Desaix ordered General Kellermann to charge the disorganised Austrian column, causing the Austrian infantry to rout in complete disorder. Zach himself was captured in the confusion. In an instant, Kellermann’s charge shifted the momentum of the battle and the French infantry advanced forward to pursue the fleeing Austrians. At this very moment, Desaix was killed by a shot to the chest.

The death of General Desaix, Jean Broc (Public Domain)

The shattered and demoralised Austrians fled back to Alessandria, having to abandon some of their guns as they went back across the Fontanone. Other Austrian units which had not been caught up in the disorder managed to form a rearguard to cover the retreat. When the demoralised and beaten Austrian army returned to Alessandria, Melas was shocked to learn of the defeat. The Austrians had suffered around 7000 casualties in total – 1000 men killed, 4000 wounded, and 2000 captured. French casualty figures were only slightly fewer. Demoralised by the setback, Melas chose not to continue the fight and capitulated, evacuating his troops and leaving restoring Northern Italy to French control.

Almost as soon as he had won his victory, Napoleon chose to return to Paris. Napoleon had driven the Austrians out of Italy and secured the victory he needed to bolster his political position in Paris. He returned to the capital on 2 July and was greeted as a hero. The War of the Second Coalition was not yet over. Archduke John of Austria still had a formidable army in Germany. It was only when General Jean Victor Marie Moreau’s Army of the Rhine defeated the Austrian Archduke at the Battle of Hohenlinden on 3 December that the Austrians agreed to peace talks. In February 1801 France and Austria signed the Treaty of Lunéville which broadly confirmed those of Campo Formio. This suited Napoleon’s purposes well enough, since he was keen on moving ahead with his agenda of domestic political reform.

Despite the later propaganda surrounding Marengo (Napoleon famously named his horse after the battle), the battle was hardly a demonstration of Napoleon’s genius for military command. Nor was it particularly great in size compared to later battles - Austerlitz, Borodino, Leipzig, Waterloo. Its significance and lies in the fact that Napoleon had come so close to losing the battle. Had he lost the battle, his small army would have risked complete destruction. Melas would have been able to consolidate Austrian control in Italy. Bonaparte’s political position was largely dependent on his reputation as a victorious general, and his authority over the army allowed him to use force when needed. The army could have easily withdrawn their support and turn to a host of equally successful generals and who might have been keen to lead their own coup. Instead, having embellished the account of the battle to give the impression that he and his Guard had performed much better than reality, Napoleon was able to increase his support and largely silence his critics. (Even this did not stop an assassination attempt in the form of machine infernale plot on 24 December 1800.) Without victory at Marengo, there would have been no Napoleonic Code, no Emperor Napoleon, and no Austerlitz.

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!