This is the second of a two part guest post by our good friend Josh Provan about Napoleon's final days in St Helena before his death on 5 May 1821. Josh is a history blogger and author who runs the Adventures in Historyland blog as well as a talented artist who has created several designs on our store, including a special Napoleon 200th anniversary design available on mugs and T-shirts. Check out other products featuring Josh's designs here.

3 May.

It had been a comparatively quiet night, but towards morning the patient’s fever increased and with it the delirium, thankfully however it was a short bout, and Napoleon managed to swallow two biscuits and an egg yolk and some wine, but his feebleness continued and even these small bites of nourishment were impossible to keep down through the continuing episodes of nausea and vomiting.

Upon hearing of the further decline of his prisoner, Sir Hudson Lowe suggested some fresh cows milk might be beneficial. Doctor Antommarchi and Doctor Arnott had a heated discussion on the efficacy of allowing Napoleon to take any, with the former arguing that the emperor was more or less lactose intolerant, in addition to the fact he couldn’t keep down the couple of biscuits he was fed every day let alone milk, which most Italians found insufferable after a certain hour.

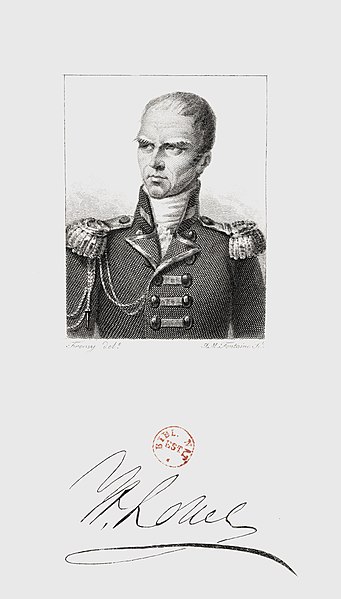

Sir Hudson Lowe, engraving by Jean Matthias Fontaine c1830.

At noon, the fever was back but now the emperor’s lower extremities were becoming cold and eventually warm cloths and towels had to be wrapped around his feet to try and alleviate this. Napoleon’s energy was being sapped by constant hiccoughs, difficulty breathing, accelerated pulse and the unchanged ‘oppression of the stomach.’

Of note is that Montholon’s typically out of sync memoir puts Napoleon trying to rise from his bed as happening on at least two occasions, once today and another on the day he died, where he said he fell on top of Montholon which slightly corresponds to the versions of Antommarchi and St Denis, but it is beyond my powers to cut through the discrepancy of accounts.

Relief was found in the small pleasure of a cup of orange flower water mixed with water and sugar which gave him great satisfaction. Two hours later he was thought stable enough to be left alone, but Abbé Vignali chose to remain with Napoleon for a few minutes after which he returned to tell the group he had administered the viaticum. This as usual is problematic in that Montholon recorded that he had an extended interview with the Abbé on the 1st of May, but we can at least be certain a private meeting did occur in his final week, which the household probably felt comforted by as at 3pm the symptoms resumed with greater force than before and the unnerving signs in his discoloured and flakey face of Hippocratic facies was observable; a sure sign of approaching death.

It may be that it was this day that Marchand and St Denis believed he was moments from death and both tearfully kissed his hand in farewell. It was never confirmed whether or not the last rites had been actually administered, but Napoleon certainly wanted it to be broadcast that he had made a last confession and received absolution before the end, Abbé Vignali never confirmed or denied it, and took the secret with him to his grave.

In moments of relative comfort, and it is doubtful Napoleon was ever truly at ease during the last days of his life, he again showed that he still maintained his mental acuity, giving commands whenever he could. Today these took the form of making sure no British doctors were allowed to see him except Arnott and asking for reassurance that those around him would respect his memory and legacy.

At around 5pm Antommarchi was called to a conference with two other British doctors and Arnott, though others said he called in other medical men to consult. Once again Marchand recorded a suspiciously similar meeting on 2nd May after a disturbed night, but it would seem that in this either he or Antommarchi are confused, nevertheless it seems many such consultations were held. Arnott had felt a fullness and tension in the belly and thought it necessary to purge the patient and a purgative of ten grains of calomel, as Napoleon refused medicine, was suggested to which Antommarchi said he objected strongly but did not prevent at 6pm.

From this point Napoleon seemed unable to swallow without water, the hiccoughs returned and between 11.30 and 12pm there was ‘abundant evacuation of matters, having the consistency and colour of pitch,’ which Arnott described as ‘remarkably fetid.’ This was confirmed by St Denis, who blamed the calomel, and lumped Antommarchi in with the decision to prescribe it. The professor himself described the episode as a ‘complete collapse.’

When Napoleon had recovered somewhat he intermittently asked for small sips of his orange flower drink which seemed to refresh him a little, and Arnott wrote that he gave him some more of the tincture of opium.

4 May.

Surgeon Major Archibald Arnott, 20th Foot, c1850-55. Anonymous.

Overcast skies added to the gloom surrounding and inhabiting the humid and uncomfortable rooms of Longwood. Mist yielded to rain showers which were blown away by the southeast wind. With the dawn, so said Antommarchi, came a storm which uprooted some trees, such as the willow Napoleon had enjoyed sitting under on fine days and also felling one of Longwood’s surviving gum trees. For Antommarchi it was all very apt but at least one longtime resident on the island swore there was never a serious storm while Napoleon was on the island.

The unpleasant ‘evacuations’ of nauseous black matter continued for an hour of the new day, and this, added to the other symptoms from 5am, completely exhausted the emperor. Through a difficult operation which required St Denis to climb onto the bars of the bed, crane down and lift the patient bodily, some of the others managed to remove the sheet he was lying on and clean him up. Napoleon seems to have been semi conscious at this point and struck St Denis on the side, calling him a rascal for hurting him. Yet the doctor still tried to feed the patient, but unsurprisingly the dying man, as much as he could, refused both medicine and broth.

A convulsive smile and a worrisome flickering of his eyes toyed at his pallid features. More dispiriting evacuations occurred but thankfully for the patient, he did not notice them for as Antommarchi put it he ‘seemed totally devoid of sensation.’

5 May.

Napoleon on his deathbed. Horace Vernet 1826.

Delirium and fever had once again overtaken Napoleon. By this point the household was exhausted from the constant vigil at the bedside, dozing only to rush to the prone figure of the emperor and search for signs of life. This night they had been able to sleep quite well as Napoleon seemed to be resting quietly. Towards 4am those on watch went to check how he was doing and discovered his breathing was so shallow as to be almost imperceptible. A light was brought and they saw his eyes where open and fixed but without recognition in them. Some sinapisms and blisters were applied for the sake of trying but there was nothing left to be done. From that moment no one left the bedside, and indeed a crowd began to gather.

At 5,30am Antommarchi heard Napoleon murmur some words which included, ‘head’ and ‘army’ and later recorded these had as Napoleon’s last words before losing the power of speech. Others recalled the name of Josephine coming up as well as similar variations of the above.

As the assembled servants and courtiers watched, Napoleon began to convulse and his lower jaw began to likewise relax and contract in spasm. The doctor pressed his fingers against the clammy skin to monitor the pulse. Trying at the carotid artery, then at the axillary and he struggled to feel the ‘vital spark’ at work. It was so faint that in another moment Antommarchi would have declared him dead, but by degrees the pulse strengthened and eventually deep sighs escaped his troubled lips.

Present at the bedside was Madame Bertrand, who in the wisdom of those caught in an emotional moment decided it was allowable to expose her children to the spectacle of Napoleon’s final struggle. As can be expected they did not take it well. The sight of the cadaverous, discoloured, faintly breathing object with the unearthly smile and staring eyes caused them to rush to the bedside and begin sobbing over the emperor’s hand.

After young Napoleon Bertrand fainted, the scarred children were taken into the garden and Napoleon struggled onwards. His pulse was wildly erratic, while spasms and convulsions distorted his features but he did not seem to be aware of anything. Every now and then he emitted sighs and mournful sounds punctuated at one point by a startling shriek. Through that last half hour, Antommarchi was constantly taking a reading of the patient’s pulse and checking his breathing, at one point he sponged his lips with the orange drink he had been fond of but nothing was swallowed. Once again Montholon steps in to confuse the matter, or perhaps it is the other way around, in saying that Napoleon was conscious enough to keep swatting his personal physician away and asking Montholon with his eyes to keep his lips moist.

According to the doctor’s watch, at 11 minutes to 6 a slight froth covered Napoleon’s lips and the pulse could not be found. His face was exhausted and drawn but at the same time calm and placid, the small convulsive smile tweaking one side of his face. Montholon wrote that he himself closed the emperor’s eyes. The Abbé kneeling at the foot of the bed bowed his head in prayer, outside, at the hour, the six o’clock gun fired its routine shot from the military camp on the ominously named Deadwood plain, as the south east wind blew against the windows. The train of mourners sadly left the room, kissing the dead emperor’s hand and the executors of his will immediately retired to read his last wishes.

About an hour after the advertisement of Napoleon’s death by Montholon, Sir Hudson came to Longwood from his residence to view the body in Company with several other officials. Lowe had been told that Napoleon’s illness would likely be fatal on 16 April, and his realisation that he would be put under severe scrutiny in this event was what had prompted that specific reference in the letter to Lord Bathurst about utilising the services of every medical person available.

After a cursory viewing, Lowe questioned the experts and staff. He wanted confirmation that the body he was looking at was both dead and that it had once contained the soul of the former emperor of the French. Having been satisfied on these points he also bluntly asserted that he could not allow the body to leave the island. This provoked a storm of outrage from practically everyone as Napoleon’s will had specifically requested burial on the bank of the Seine, but Lowe was adamant and in the matter of Napoleon’s fate his word was law. Napoleon would be buried on the island wherever his suite wanted. Lowe further pressed to have the body ‘opened’ for inspection immediately, but in this he deferred to the medical men who said that it was too soon after death and they would have to wait, likewise Bertrand, Montholon and Louis XVIII’s Commissioner the Marquis de Montchenu also objected. At around 11am body was washed and shaved and placed on a different bed to the one he had died in. Antommarchi managed to collect some plaster and took a mould of Napoleon’s face and gave the body a visual inspection, which is how we know that his exact height was 5 feet 6 inches and that his hair was chestnut in colour.

So what of the causes that brought him to this end?

At 2pm on 6 May, Five medical men, including the surgeon of the 66th Foot, the chief medical officer of the East India Company on St Helena and Antommarchi performed the autopsy in the drawing room of Longwood, with General Bertrand and Comte Montholon standing as witnesses. A large cancerous ulcer had spread through the majority of his stomach, which was identified even by Antommarchi to be the ‘seat of extensive disease.’ Most of his vital organs were encased by a layer of fat up to an inch thick and stones were found in his bladder. Practically everything pointed to the insufferable torture he had endured during the last months of his life.

At the time the logical medical conclusion was to attribute stomach cancer or hepatitis to Napoleon’s death. O’Meara and Antommarchi had treated him for liver disease and the latter had believed that hepatitis was the culprit. Though Napoleon said his pain emanated from his stomach, the study of cancer was in relative infancy and no one really had a clue about the massive tumour growing there. Dr. Arnott had actually been the first to suggest cancer but few thought this was the case and indeed Arnott, though knowing the patient was seriously ill, told Napoleon he was suffering from dyspepsia to give him hope, then inexplicably told Lowe that it was hypochondria, and stuck to this until he became clearly terminal and even then was only in the autopsy that he realised how badly damaged Napoleon’s digestive organ was, and that he had been correct to fear it was cancer.

Although there is much to say about conspiracies and the like, this medical controversy is where we will leave the subject, and now we can return to debating and eulogising a not so ordinary life.

‘Well gentlemen,’ Sir Hudson Lowe told some of his staff shortly after the melancholy event, ‘he was England’s greatest enemy, and mine too, but I forgive him everything. On the death of a great man like him, we should only feel deep concern and regret.'

With thanks to Napoleonic Impressions for hosting and Lally Brown for help with the accounts. Highly recommended is the blog of Shannon Selin (https://shannonselin.com/) and the British Napoleonic Bicentenary Trust (https://www.napoleon200.org/)

Sources:

Antommarchi., The Last Days of the Emperor Napoleon, Vol. II.

Arnott., An Account of the Last Illness, Decease, and Postmortem Appearances of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Forsyth., History of the captivity of Napoleon at St. Helena; from the letters and journals of the late Lieut.-Gen., Sir Hudson Lowe.

Montholon., History of the Captivity of Napoleon at St. Helena, vol III.

O’Meara., Napoleon in Exile, or A Voice From St. Helena.

Seaton., Sir Hudson Lowe and Napoleon.

St. Dennis., Napoleon from the Tuileries to St. Helena.

Stokoe/Frémeaux., With Napoleon at St. Helena: being the memoirs of Dr. John Stokoe

Young, Norwood., Napoleon in exile: St. Helena (1815-1821) vol II.

The first five Napoleonic Impressions customers based in the UK who spend at least £30 can receive a free copy of historical fiction novel Napoleon's Drop by Michael Fass, set during Napoleon's exile in St Helena. For more information about the offer, click here.

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!