In our previous post we gave a biographical overview of the life of Marshal Bernadotte, later King Charles XIV of Sweden. This week we assess his controversial legacy. Was Bernadotte any good as a military commander? Was he a traitor to Napoleon and to France? Did Bernadotte only act in the interests of Bernadotte?

The Arc de Triomphe is one of France’s most famous landmarks, and serves as a reminder of France’s military glory during the turn of the 19th century. The walls of the arch are inscribed with the names of dozens of leading generals of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. These include 24 of the 26 men Napoleon appointed to the venerated rank of Marshal of France. The two exceptions are Marmont and Bernadotte, both considered traitors to France. While Marmont was censured for abandoning the defence of Paris in 1814 and spent the rest of his life in exile, Bernadotte had become Crown Prince of Sweden in 1810 and took up arms against his native land as part of the Sixth Coalition.

Sweden had approached Bernadotte with their offer in part due to the desire to maintain good relations with Napoleonic France. Despite his mixed record as a Napoleonic Marshal, Bernadotte was a close relative of the Bonaparte family. As we have explained in our previous blog post, while Napoleon initially treated the idea with much skepticism, he soon came to realise how it could benefit him. Not only did he believe that Sweden would finally comply fully with the Continental System, but it also kept a troublesome general at arm’s length, preventing him from causing any trouble in Paris.

It is also important to consider Bernadotte’s personal position when he was approached by the Swedes with the offer. After being ordered back to Paris after Wagram, and dismissed from his command in the Netherlands, it is unlikely that Napoleon would ever have employed him in the field again. Facing the prospect of a rather mundane retirement or serving in minor administrative roles, the opportunity to become King of Sweden was a godsend for Bernadotte. Thus, the arrangement suited all three parties: Sweden, Napoleon, and Bernadotte.

Events proved that Napoleon was mistaken in his belief that Bernadotte would stop Sweden from trading with Britain, or that Franco-Swedish relations would remain amicable. Did this make Bernadotte a traitor to France? At their final interview, Napoleon explicitly attempted to extract a promise from Bernadotte not to take up arms against France. Bernadotte refused, saying only that he would do what was in the best interest of his Swedish subjects. By then it was too late for Napoleon withdraw his blessing. Perhaps Napoleon believed that Bernadotte would not dare to take up arms against him.

While war with France was hardly in Sweden’s interests, it was very much in Sweden’s economic interests to continue trading with Britain through Swedish Pomerania. This prompted Napoleon to order Marshal Davout to occupy Swedish Pomerania. Not only was this an act of aggression on Napoleon’s part, but given Bernadotte and Davout’s previous enmity, it was designed to anger Bernadotte. Rather than forcing Bernadotte to back down, the Crown Prince opted to align closer to Russia. Despite this, Napoleon still hoped that Sweden would join his side in the invasion of Russia in 1812.

Bernadotte’s behaviour is entirely consistent with the fact that unlike Napoleon’s relatives on the thrones of Spain (Joseph), Naples (Murat), Westphalia (Jerome), all of whom had become kings through conquest, Bernadotte was invited by the Swedish Riksdag (Parliament). If he had to choose between the interests of Sweden and those of Napoleon, he would naturally side with the Swedes. Unlike Bonaparte, Bernadotte was no dictator and understood the risks of ignoring Parliament. (Contrast this with the experience with Louis Bonaparte, who had attempted to work with Dutch elites as King of Holland but was dismissed by his brother in 1810.)

Of course, for his former comrades in 1813, Bernadotte was a Frenchman leading an army of Prussian, Russian, and Swedish troops against fellow Frenchmen. Such feelings were easily shared among the men and women who lived in northeast France in early 1814 as Bernadotte’s Army of the North crossed the border into France. Bernadotte himself tried to demonstrate that he had no dispute against France, only against Napoleon, but this had understandably fallen on deaf ears.

With the benefit of hindsight, some observers argue that Bernadotte’s conduct at Jena-Auerstedt and Wagram demonstrates that he was already intent on undermining Napoleon. At worst it was treachery, at best incompetence, or so the argument runs. While Bernadotte’s record as Marshal of France was certainly far from impressive, at closer examination he was not solely to blame.

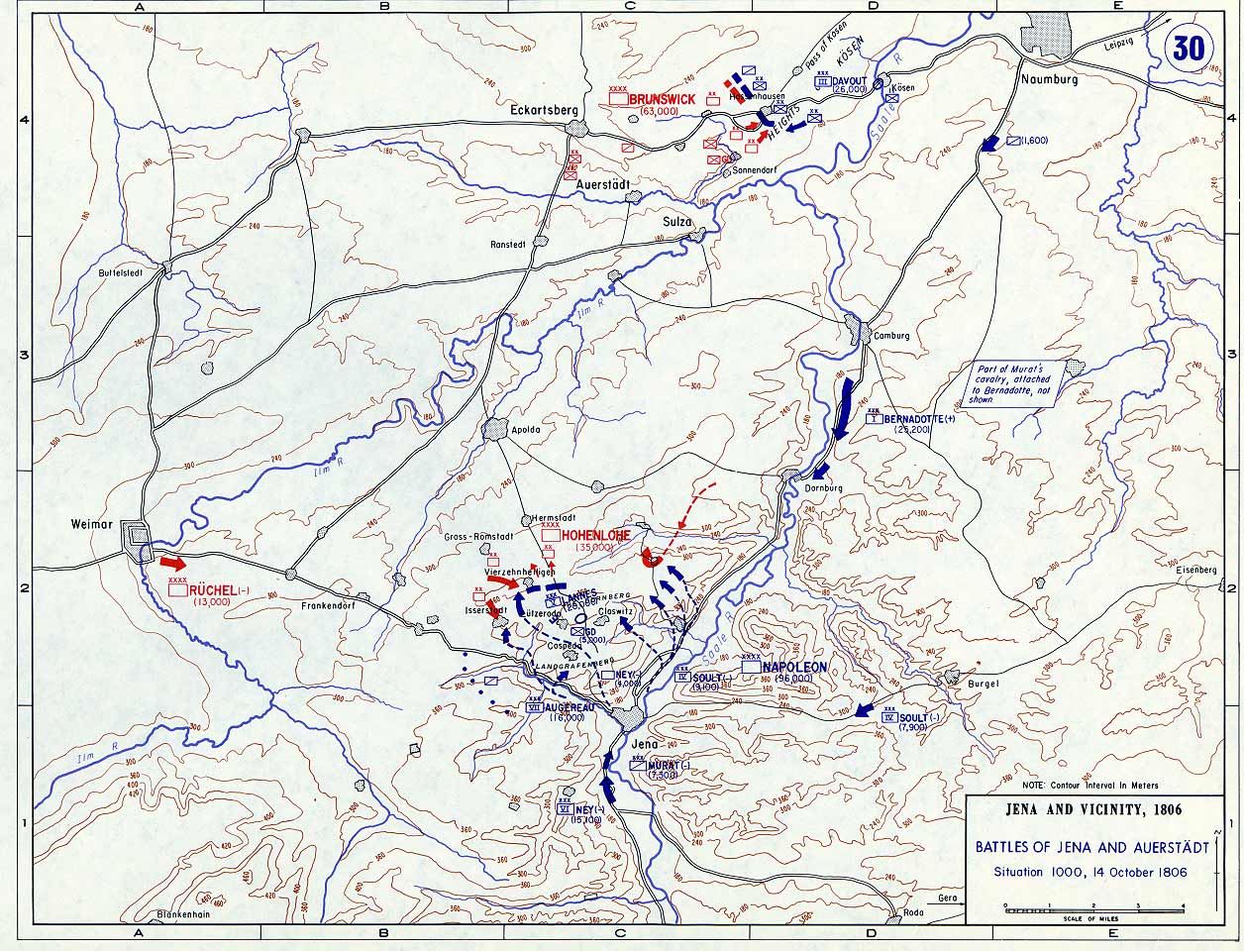

With the benefit of hindsight, Bernadotte is often criticised for his failure to assist Davout at the Battle of Auerstedt in 1806. However, on the eve of battle on 13 October, Napoleon had expected the Prussian army to be concentrated around Jena. Davout was expected to march west to the enemy’s rear at Apolda, while Bernadotte following behind would turn south towards Jena, spending the night at Dornburg. At 10pm in the evening, Davout received a postscript to his orders that ‘If the Prince of Pontecorvo [Bernadotte] is still with you, you can march together. The Emperor hopes, however, that he will be in the position which he has assigned to him at Dornburg.’

As Bernadotte had been delayed, he was still close enough to Davout for the latter to pass on the instruction to him. As it was not an explicit order for him to accompany Davout (which would have slowed the progress of both corps), and Napoleon’s preference was for him to be at Dornburg, Bernadotte chose to follow Napoleon’s original instructions. During the morning of 14 October Davout had no inclination that he would run into the main Prussian army at Auerstedt. By the time Davout realised the size of the enemy force he had engaged, Bernadotte would have been too far away to help. If Bernadotte is to be criticised for anything, it is the failure to participate at the Battle of Jena rather than his absence from Auerstedt.

Battles of Jena and Auerstedt

That Davout managed to prevail alone against Brunswick could be considered good fortune for both men. The former’s victory at Auerstedt would not have so special if his army had been twice as large, while the defeat of the Prussians allowed Napoleon to overlook Bernadotte’s absence from both battles. Bernadotte redeemed himself to a large extent with his relentless pursuit of the defeated enemy, ensuring that they could not regroup and give battle. He could not be faulted for his absence at Eylau since his orders never reached him, while the neck wound he suffered at Spanden which caused him to miss Friedland showed that he was not lacking in bravery.

In spite his absence from Jena and Auerstedt, Napoleon kept Bernadotte in the army. Bernadotte’s performance at Wagram three years later would see him suffer much more serious consequences. Bernadotte’s men were in the centre of the French line around the village of Aderklaa. On both days of the battle Bernadotte’s Saxons suffered considerable casualties, prompting him to fall back and abandon the village. Bernadotte had already criticised Napoleon’s handling of the battle on the first day, and this compounded his miseries. The final straw for Bernadotte his proclamation at the end of the battle to his Saxons that they had fought well and made the major contribution to the victory.

Bernadotte was not at fault for having inexperienced men under his command whom he had little time to train. It was also unfortunate that the white uniforms of the Saxons were difficult to distinguish from those of the Austrians, leading to several friendly fire episodes. Napoleon famously said that he preferred to have lucky generals than good ones. At Wagram, Bernadotte proved especially unlucky. As for Bernadotte’s proclamation to the Saxons, he was hardly the first general in history to lie about the contribution of his men in battle. Napoleon himself was the master.

Any examination of Bernadotte’s military capabilities must go beyond his record as a marshal. Bernadotte was not only a marshal because he was related to the Bonaparte family, but had proven a very successful and inspirational general in the Revolutionary Army. His tactical abilities and his personal bravery were never in doubt. He was respected and admired by his men and may have pulled off a coup in the manner of 18 Brumaire.

General Bernadotte on horseback during the Italian campaign

Bernadotte’s record as Crown Prince of Sweden during the campaigns of 1813-14 is rather complicated. His insights into Napoleon and the marshals proved invaluable when the allies formulated the Trachenberg Plan. Bernadotte knew intimately of the mutual jealousy and suspicion among the marshalate, and that only Napoleon’s presence could make them fight effectively as a team. With three allied armies advancing on three fronts, Napoleon could not expect to be everywhere at once. Thus, while Napoleon did prevail against Schwarzenberg at Dresden, Macdonald was defeated by Blücher at the Katzbach, while Oudinot and Ney were defeated by Bernadotte’s at Grossbeeren and Dennewitz.

Nevertheless, there is much to criticise about Bernadotte’s performance in 1813-14. It was abundantly clear to the allies, especially Blücher, that he was far more interested in using his 30,000 Swedish contingent for the conquest of Norway. To this end, he proceeded with an abundance of caution, always fearful of his rear, and relied on the Prussian and Russian contingents in the Army of the North to win his battles. Even at Leipzig, he was only persuaded to launch his attack when Blücher agreed to give him half his force. Following Leipzig, Bernadotte’s Army of the North went back north to besiege Marshal Davout at Hamburg. It was probably to the allies’ benefit that the most cautious commander of the three armies was tying up Napoleon’s best marshal.

While he enjoyed a reputation in his adopted homeland as a military hero, and was well-liked by both the British and Russians, some of his allies would have sympathised with Napoleon when it came to Bernadotte’s reliability and competence as a commander. By 1814 Tsar Alexander and Napoleon would not have agreed on much, but they may have been of a similar mind that Bernadotte was a political opportunist who was primarily motivated by self-interest.

While Alexander had flattered and indulged Bernadotte, making promises he could not keep, Napoleon alternated between keeping him under close supervision (1805-09) and sending him far away (1799-1804 and from 1809). As mentioned above, it was therefore very much in Bernadotte’s personal interests to become Crown Prince of Sweden in 1810. It is hard to imagine the likes of patriotic Frenchmen such as Marshal Macdonald or Jourdan making the same decision. Even after Bernadotte had been securely installed in Stockholm, he seriously entertained hopes of being a constitutional king of France.

Bernadotte’s political ambition manifested itself even before he became a marshal. His brief stint as minister of war caused Barras to fear a military coup. He frequently turned down appointments hoping for something better. While he seemed genuinely attached to the ideals of the French Revolution in his early years, his undiplomatic conduct as ambassador in Vienna could have been a ploy to be recalled and given an army command. Similarly, Bernadotte refused to go to America when he learned of the Louisiana Purchase and the downgrading of his status from governor to ambassador.

Marshal Bernadotte

Even so, Bernadotte was hardly alone among Napoleon’s marshals in being politically ambitious. Marshal Murat, another of Napoleon’s brothers-in-law, had been made King of Naples, and in 1814 concluded a separate peace with Austria in order to preserve his throne. When Murat came to realise that the Austrians might not keep the agreement, he rallied to Napoleon after his escape from Elba but was rejected as a turncoat. A forlorn attempt to unite Italy led him to a firing squad in October 1815. Bernadotte’s political instincts were far better, allowing him to enjoy a relatively peaceful 26 years as King of Sweden.

Like much of the marshalate, Bernadotte failed to get along with his peers. As we have seen, his relationship with Davout was especially bad. This in itself is not a surprise since Davout failed to get along with pretty much everyone. Bernadotte is said to have refused to respond to Davout’s call for assistance at Auerstedt as it would have meant taking orders from someone of equal rank. Such behaviour violated the spirit of Napoleon’s battalion carré, which stipulated that his marshals should march to support another who was attacked by the enemy. Davout hoped that Bernadotte would be court-martialled and shot for his failure to help at Auerstedt, and Napoleon might have briefly considered it. Yet this was just an early example of marshals failing to work together when Napoleon was not at hand.

In certain respects, Bernadotte’s character proved far more admirable to his colleagues. Bernadotte was among a select number of marshals who avoided looting and pillaging. This stood in contrast to Marshal Soult, nicknamed ‘King Nicolas’ for the wealth he had amassed in Spain, or Massena, who was as talented at stealing as he was at fighting. While on campaign Bernadotte ensured that his men would keep their discipline. This quality also made him an effective administrator in northern Germany. Indeed, his respectful treatment of Swedish officers had been a factor in his election as Crown Prince. The offer from the Swedish Parliament was a slice of good fortune which he did not expect, but gleefully took full advantage.

We have argued over the course of this blog post that Bernadotte cannot be considered a traitor. Napoleon himself admitted on Saint Helena that Bernadotte “never promised or declared an intention to stay true. I can therefore accuse him of ingratitude, but not of treason.” Nevertheless, Bernadotte continues to be singled out while Murat’s disloyalty is conveniently forgotten.

Bernadotte's critics, having convicted him of treason, point to his conduct at Auerstedt and Wagram as evidence of pre-conceived designs to undermine Napoleon. As we have seen, Bernadotte’s refusal to aid Davout was partly motivated by personal animosity, but he was far from unique in his display of impertinence. His decisions at Wagram were a combination of bad luck and his desire to avoid further needless casualties. He was an average marshal at best, but remained a competent and inspirational commander.

There is no doubt, however, that Bernadotte made many choices to advance his career, with little consideration for his family, Napoleon, or France. In this respect, Bernadotte was no better or worse than Napoleon himself, who proved a master of political intrigue during his rise to power. While Napoleon leaves behind a greater legacy, Bernadotte proved to have superior political instinct at the time. After refusing several compromises in 1813 which could have kept him on the French throne, Napoleon ended his life in exile in Saint Helena, while Bernadotte became a well-loved King of Sweden, founding a dynasty which continues to reign to this day. In their lifetimes, Bernadotte proved to be Napoleon’s more successful alter ego.

If you are a Bernadotte fan and enjoyed reading this, check out our Bernadotte matryoshka mug:

Share and get 15% off!

Simply share this product on one of the following social networks and you will unlock 15% off!